The very strange history of Charlotte Atkyns

She was the daughter of Britain’s first prime minister, an actress, lady of Ketteringham Hall, and she tried to save Marie Antoinette from the guillotine. It’s a great local story – but is any of it true?

The church of St. Peter at Ketteringham may be one of the trickiest to find in Norfolk, but it has one of the best collections of medieval and Flemish glass in the county, and its memorials – covering some 500 years in the lives of four prominent local families – are among the country’s most interesting. And quirky. Perhaps the most intriguing is a relatively plain tablet with a particularly curious inscription:

“In memory of Charlotte, daughter of Robert Walpole and wife of Edward Atkyns Esq of Ketteringham. She was born 1758 and died at Paris 1836 where she lies in an unknown grave. This tablet was erected in 1907 by a few who sympathised with her wish to rest in this church. She was the friend of Marie Antoinette and made several brave attempts to rescue her from prison and after that Queen’s death, strove to save the Dauphin of France."

It sounds a quite incredible story; a young woman from west Norfolk (the daughter of Britain’s first Prime Minister no less!) who became friends with the doomed Queen of France and tried to save her from the guillotine during the French Revolution. And at first sight, the story really is a remarkable one.

It seems that Charlotte Walpole had a short-lived career as an actress on the London stage at the Drury Lane Theatre – her two-year career ending only because Sir Edward Atkyns of Ketteringham Hall fell in love with her and married her in June of 1779. Unfortunately, the former actress wasn’t accepted by Norfolk society, and as her husband was suffering heavy debts at the time the couple decided to move to France.

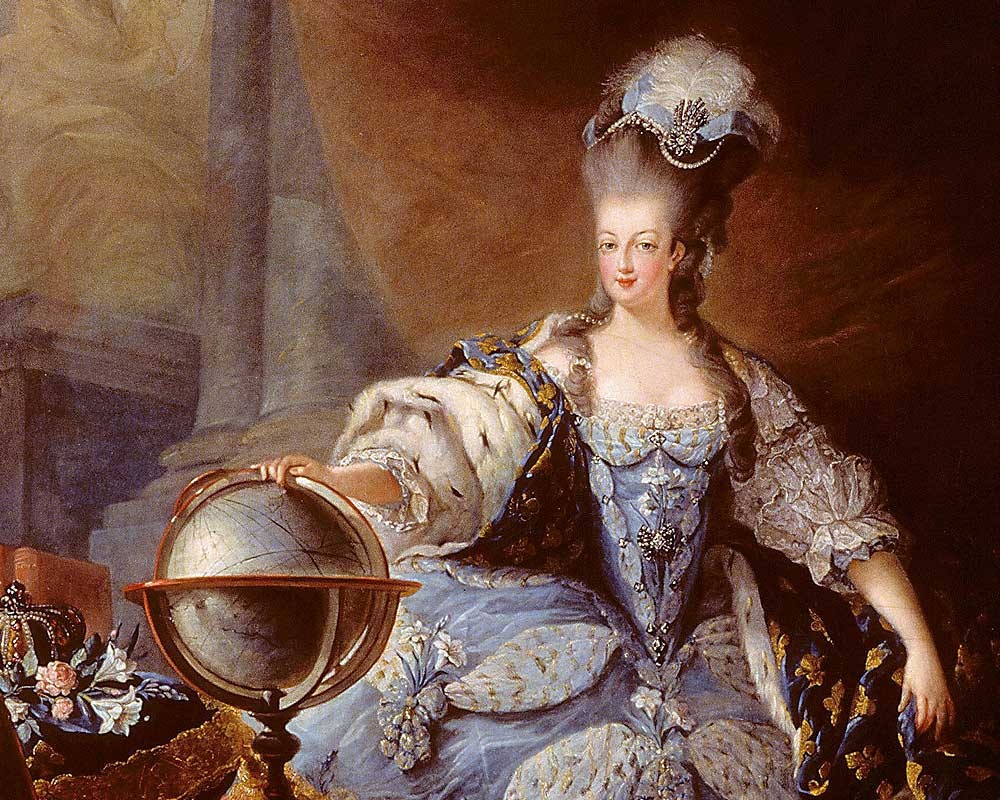

The newlyweds received a warm welcome in France, and Charlotte – described as “pretty, witty, eccentric and impressionable” – became friends with the Duchess of Polignac, who was in turn a close friend of Queen Marie Antoinette. Apparently, from the moment the Duchess introduced Charlotte to the French monarch, the woman from Norfolk was enchanted and became an intense admirer of the Queen.

When the French Revolution broke out in 1789, Charlotte and her husband moved from Versailles to Lille, and it was there she was recruited as a spy by her Royalist lover Louis de Frotté – a role she continued after returning to Norfolk with her husband in 1791.

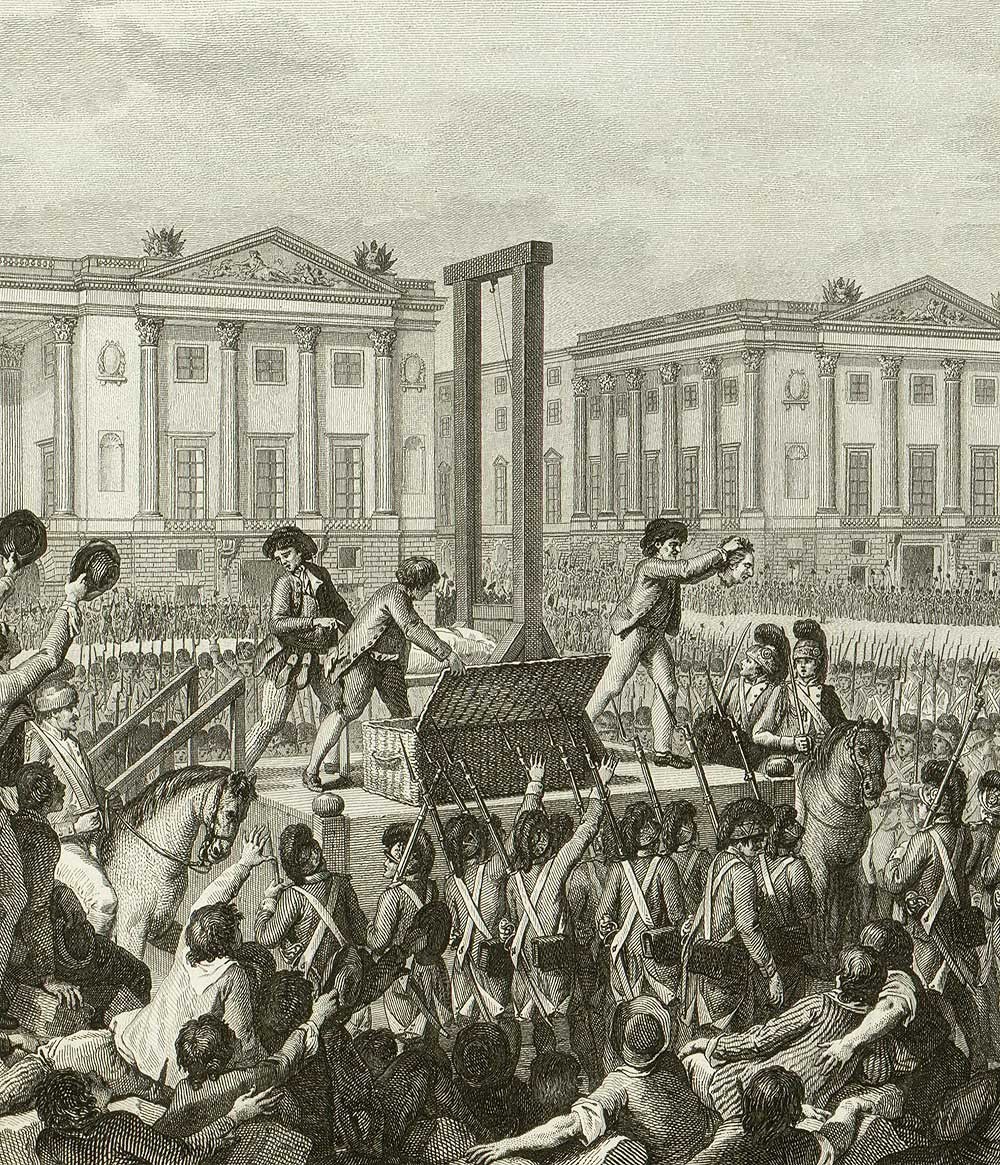

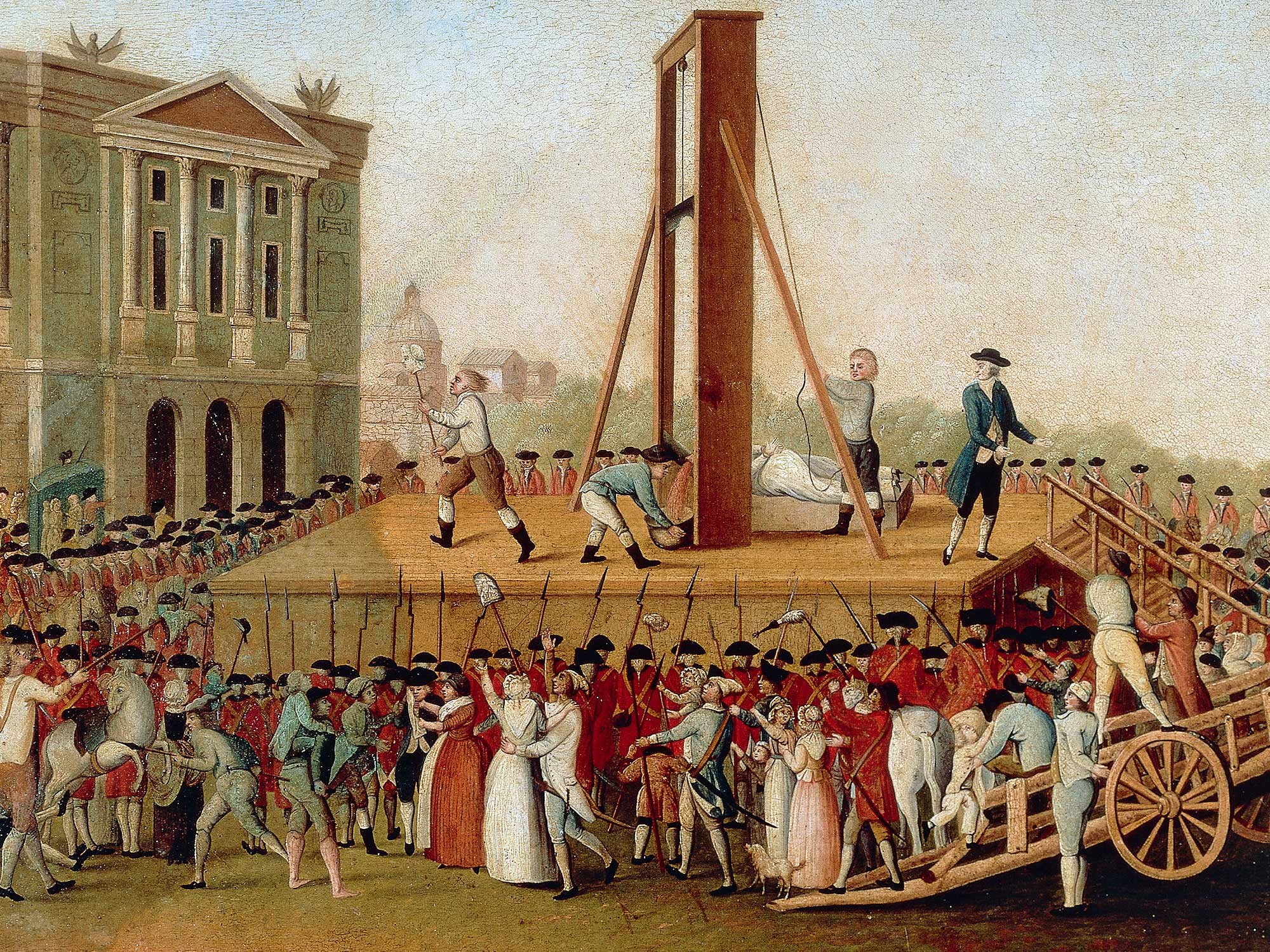

In January 1793, the French king Louis XVI was guillotined in a public square in Paris – and most people gave up any hope of being able to save his Austrian-born wife from the same fate. Not Charlotte Atkyns, however.

Back in Norfolk, in the safe surroundings of Ketteringham Hall, she decided to travel back to France and attempt to save Marie Antoinette by gaining access to the prison in which she was confined.

It was an audacious plan, and wasn’t helped by the fact that Charlotte barely spoke French and that most of her friends (who had by now escaped to England) tried to dissuade her.

“You will hardly have arrived before innumerable embarrassments will crop up,” one wrote. “If you leave your hotel three times in the day, or if you see the same person thrice, you will become a suspect. If you wish to be useful to that family, you can only be so by directing operations from here – instead of going there to get guillotined.”

Charlotte was nothing if not persistent, however, and she duly travelled to France – despite the fact that Marie Antoinette had recently been moved to a more secure prison after another rescue attempt had failed.

By somehow gaining the confidence of a prison official to open the doors of the prison (by using her old acting skills, perhaps?) Charlotte managed to dress up as a member of the National Guard and meet Marie Antoinette.

She’d been warned not to exchange any words with the imprisoned Queen, but Charlotte had hidden a note explaining the details of her rescue attempt in a bouquet – which she then dropped in all the excitement. Before the guards could grab the note, Charlotte swiftly grabbed it and swallowed it – before being equally swiftly thrown out of the prison.

She wasn’t giving up that quickly, however. Charlotte then managed to obtain an hour’s audience with Marie Antoinette at a cost of 1,000 gold coins – during which time she planned on swapping clothes with the Queen, who would then leave the prison in disguise.

If she thought her plan would work, Charlotte would have been disappointed to find Marie Antoinette was rather obstinate – she refused to leave her children and “would not, under any pretext, sacrifice the life of another.” It was a costly miscalculation. In trying to save the French Queen, Charlotte had bankrupted the Atkyns’ family fortunes, mortgaged the Ketteringham estate, and spent an extraordinary £80,000, the equivalent of some £15 million today.

And it was all in vain; Marie Antoinette was guillotined at 12.15pm on 16th October 1793, famously apologising to the executioner for stepping on his foot while climbing the scaffold. As for Charlotte Atkyns, it appears she never returned to Norfolk; remaining in Paris until her death 43 years later – and being buried there in an unmarked grave.

It’s a wonderful and dramatic story, but unfortunately it’s one with more than a few holes in it.

Ultimately, all the source material for Charlotte’s adventures come from Charlotte herself – and there are a number of indications that she wasn’t actually in Paris in 1793 as she claimed. There’s no independent evidence of her ever having been at Versailles or of meeting Marie Antoinette, and the only references to their friendship appear in letters from eminent people that Charlotte actually wrote to herself.

As for being the “daughter of Robert Walpole” (as her 1907 memorial in Ketteringham’s church has it) it seems to be an assumption by subsequent generations that Charlotte was related to the man who built Houghton Hall and became Britain’s first Prime Minister. It’s an assumption without any basis in fact, however – because not only did Walpole never have a daughter called Charlotte, he died 13 years before Charlotte Atkyns was born.

His son was also called Robert, but he had no daughters either.

The truth of Charlotte’s origins can be found in an obscure book with the unwieldy title of A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers & other Stage Personnel in London, 1660-1800.

Charlotte was actually the daughter of William (not Robert) Walpole, and instead of hailing from west Norfolk the family actually came from the west of Ireland.

Charlotte made her acting debut in Dublin, but she did enjoy a brief career in London – during which time she was praised for her acting skills in both female and male roles. Of perhaps major significance in determining the truth (or origins) of her adventures, one of the book’s rare engravings shows Charlotte Walpole as ‘Nancy’ in an obscure play called The Camp – and she’s dressed as a soldier.

The ‘real’ Charlotte Atkyns and her husband certainly spent time in France shortly before the Revolution, but they were more concerned with getting out of financial difficulties than political intrigue.

“She was a player,” wrote Lady Jerningham (who knew the couple) from Lille in 1784. “You may remember to have heard of her, and Atkyns was always a great simpleton – or else he wouldn't have married her.”

The notion that Charlotte may have created a rather fanciful legend around herself from her early acting experiences is a disappointing way to end the story, but it’s one that unfortunately may not be too far from the truth.