A flaming catastrophe and a town transformed

From anguish and ashes to beautiful architecture: exploring the astounding legacy of The Great Fire of Holt

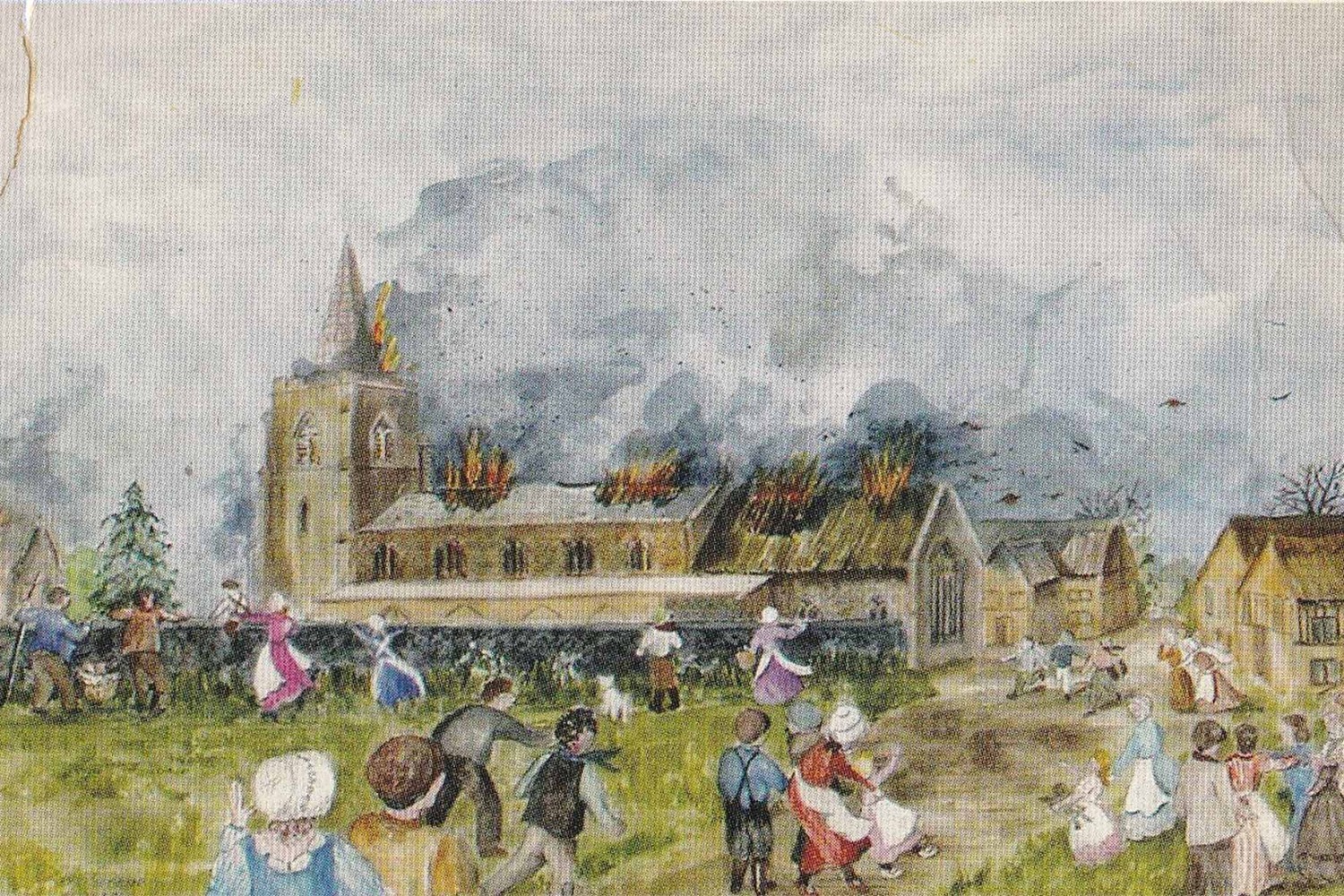

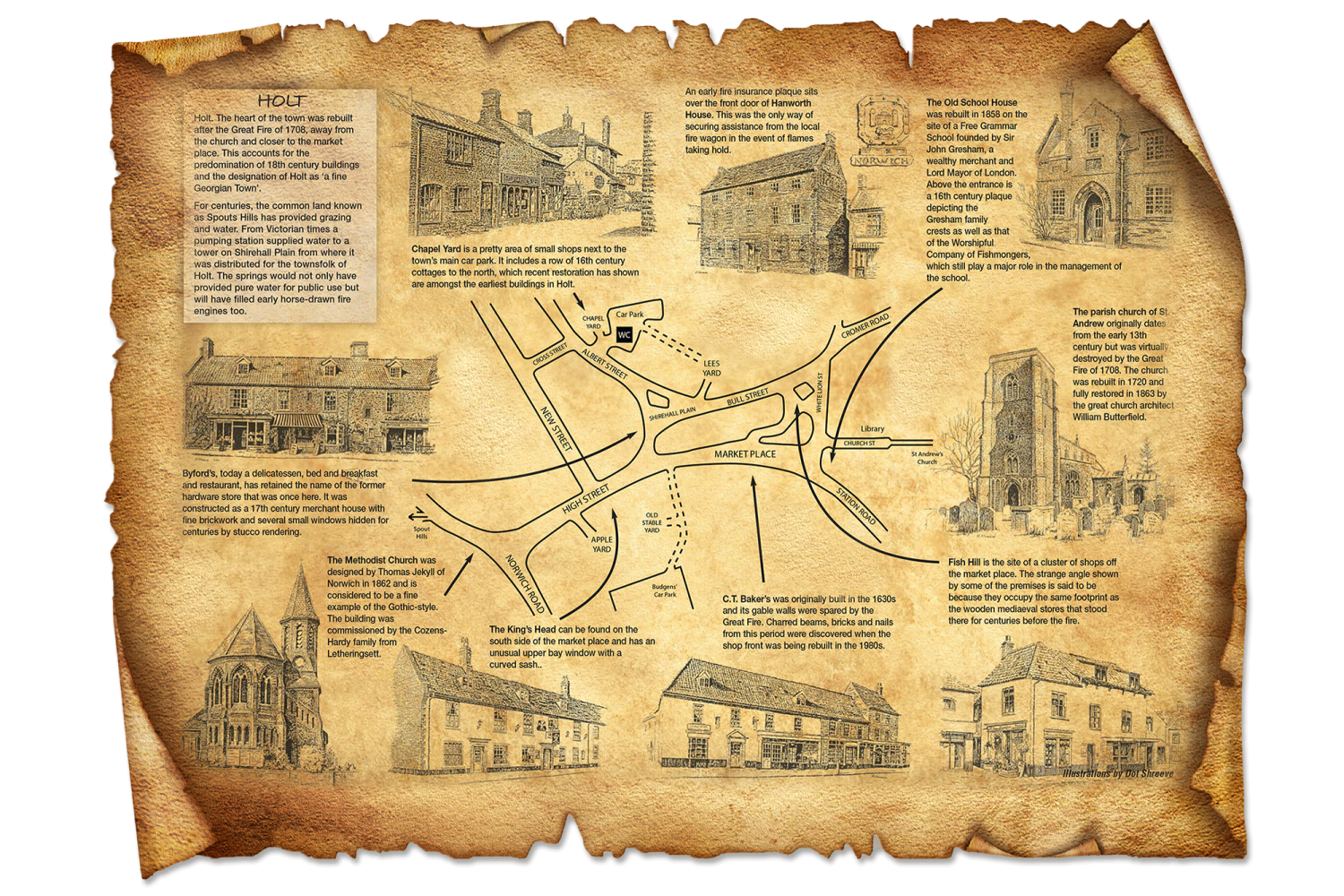

ABOVE: Holt’s Market Place and High Street are predominantly Georgian, having been rebuilt following the fire. Artist Dot Shreeve’s impression of the fire engulfing the church.

Admired for its elegant Georgian architecture, charming independent shops and idyllic countryside surroundings, Holt is considered to be one of the most attractive towns in North Norfolk. As you stroll through its cobblestone streets you’ll discover a fabulous blend of art galleries, boutiques and vibrant tearooms tucked away in atmospheric Victorian courtyards. Bursting with fresh flowers and bustling markets in the summer and twinkling with festive fairy lights over Christmas, it’s an enchanting setting with a wonderful sense of character. However, one merry May Day 316 years ago, the town was lit by a more ominous glow. A devastating fire swept through the streets with alarming speed and ferocity, razing most of Holt to the ground in less than three hours.

The Marketplace was bustling with life on that fateful Saturday in 1708. Farmers, fishermen craftsmen and traders from nearby villages had gathered, their wooden stalls laden with a fine array of goods and fresh produce. The sun had shaken off the dreary cloak of winter and bathed the cobbles in a golden hue; spring was in full swing and spirits were equally bright. Cheerful chatter filled the air as people mingled and browsed, loading baskets with homegrown delights and handcrafted gifts. Amid the jovial shouts and good humour, no one saw how the ferocious fire started.

Contemporary reports state the blaze spread so swiftly that butchers did not have time to salvage their meat from their stalls. Flames shot up from the market stands and, propelled by a strong wind, raced through the rows of timber framed houses in the town. There was little available water apart from the spring upon Spout Common, but this was too far away to be of practical use during the escalating emergency.

Flying sparks caught the thatched chancel of the nearby church of St Andrew, and soon the entire building was ablaze. The lead roofing of the aisles melted and collapsed onto the stone walls, cracking them to pieces. Merciless flames spread up to the steeple and the bells came crashing down from their wooden frames.

Miraculously, nobody was killed or even injured – but the aftermath of the brutal blaze was a scene of utter devastation. Homes and businesses were reduced to ashes and the blackened streets echoed with cries of despair.

Holt was almost entirely destroyed, with damage estimated at around £11,258. It was a tremendous sum for a small market town at the time and the repairs required were extensive, but the spirit of the resilient local community formed a spark that couldn’t be extinguished.

ABOVE: A copy of a sign that proud local history group The Holt Society put up in Shire Hall Plain.

Over the next century, the town arose from the carnage the great fire left in its wake. Rebuilding was largely driven by funds raised through a Royal Brief, a document which urged office holders, clergy, nobility and individuals to promise financial support to a stricken community. Such Briefs were granted to Holt in the immediate aftermath of the disaster (1709) and later (1723), when a concerted effort was made to restore the church. Many dedicated parishioners also contributed to repairs and skilled local tradesmen assisted with rebuilding homes and businesses, making use of more resilient materials such as brick, stone and flint. This accounts for the predomination of 18th century properties constructed with similar architectural styling and led to the designation of Holt as ‘a fine Georgian town.’

The resurrection of the gutted parish church was a long-term effort, requiring significant extra funding and support. The chancel was repaired to hold just a quarter of the congregation in the instant aftermath of the fire and a new bell was hung in the tower a few years later. The second Royal Brief garnered support from several notable contributors including Sir Robert Walpole (first Prime Minister of England) and Viscount ‘Turnip’ Townshend (Secretary of State), each giving a silver communion plate and £50. The chief philanthropist was none other than the Prince of Wales, soon to become King George II, who donated an engraved silver flagon for the communion wine and £100. These gestures of generosity saw Holt’s beloved church of St Andrew regain elements of its former glory, with extensive rebuilding taking place in the 1720s. A full restoration and internal refurbishment was completed in 1864 by the renowned Victorian architect Sir William Butterfield, resulting in the splendid edifice cherished by locals and admired by visitors today.

Interestingly, it’s believed that if the blaze hadn’t almost completely destroyed Holt, it would now look like the Suffolk village of Lavenham – full of beautiful medieval timber-framed houses and cottages. However, with its Georgian grandeur now forming the heart of its unique character and a hallmark of its enthralling past, the town is not to be outdone.

The Great Fire of Holt is a story not of what was lost but of what was gained. It’s a tale of transformation, where the warmth of community and the strength of local spirit turned what could’ve been remembered as the town’s gravest tragedy into an inspiring legacy of hope.

PICTURE: John Chapman & staff outside his Bakery in Fish Hill c1906. It’s thought that the fire may have started here in a brazier, but no one knows its origin for certain.