The west Norfolk coast: a literary sense of place

Heacham, Snettisham and Hunstanton are blessed with natural beauty and fascinating histories, but as Ian Duckett explains they also have their own place in a long literary tradition

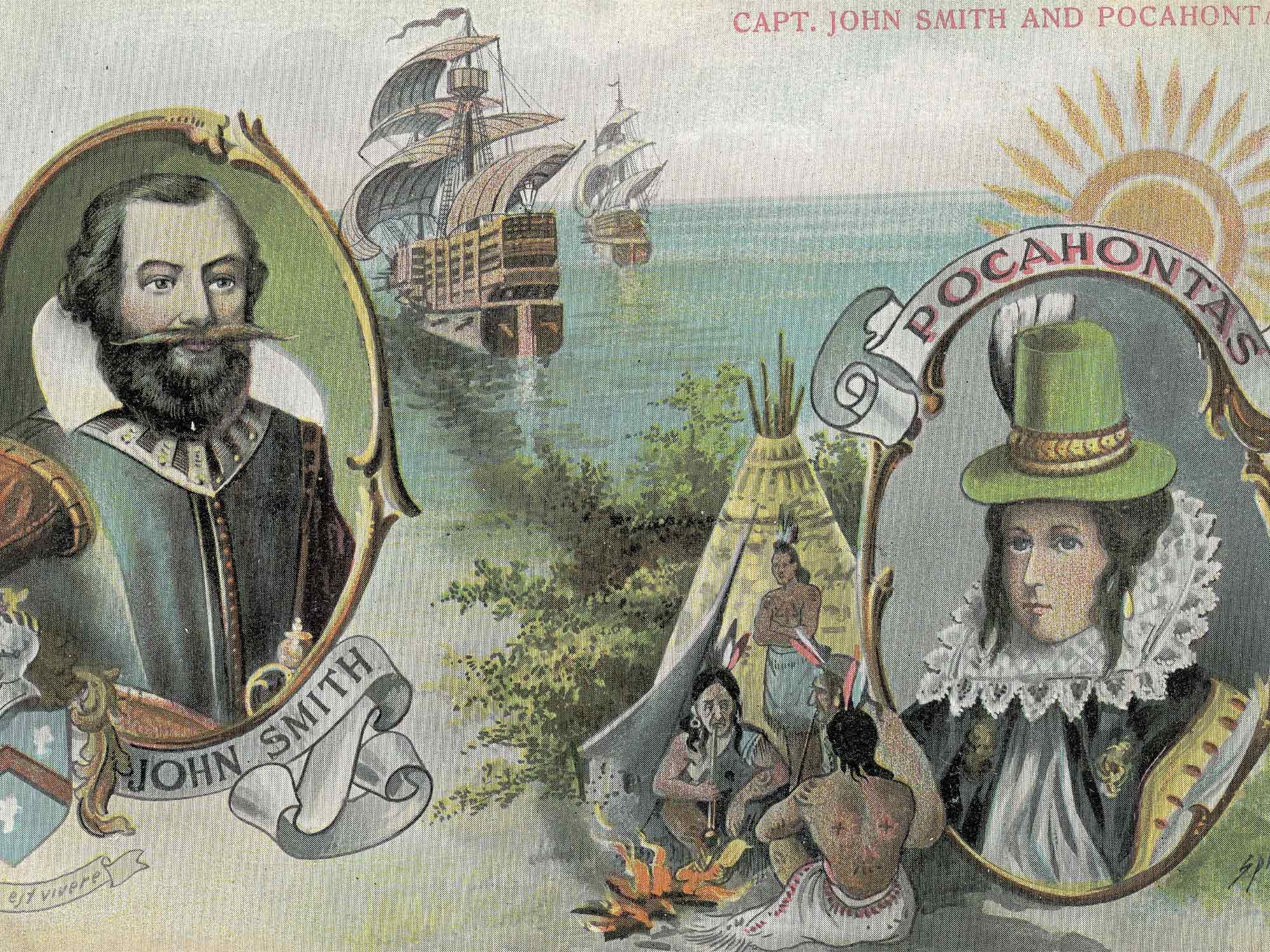

There’s no shortage of legends and stories from the villages of Heacham and Snettisham and the town of Hunstanton and it’s hardly surprising. Snettisham is mentioned in the Domesday Book, Dersingham abounds with rumours of piracy and smuggling, the native American princess Pocahontas (pictured here) married a Heacham man, and King John may have lost his treasure (and his kingdom) on the sand bank off Hunstanton.

But apart from occasional mentions in the crime novels of Elly Griffiths (in which one of the central characters is a Heacham-born police officer) there’s little to suggest a literary sense of place for these charming coastal locations.

Though the evidence is inconclusive, it’s argued that the Puritan colonisers of America influenced Shakespeare and provided the creative spark for The Tempest - the hurricane that shipwrecked Heacham’s John Rolfe supposedly inspired Shakespeare’s play and it’s likely the playwright was familiar with the exotic nature of the story of Pocahontas and her fundraising on behalf of the beleaguered colonials under her married name of Rebecca Rolfe:

O wonder!

How many godly creatures are there here!

How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world,

That has such people in’t.

- The Tempest V.i. 184–187

The relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith is very similar to the relationship between Miranda and Ferdinand; both women teach their culture and language to men who are outsiders.

Furthermore, both relationships are frowned upon by their respective fathers. Caliban is an early example of a literary staple (the ‘noble savage’) and Pocahontas can certainly be said to have been a civilising influence on the settlers in the New World.

Through the character of Ariel there is the ancient tree - and Heacham Hall (the family home of her husband) claims to have a mulberry tree planted by Pocahontas herself. At the very least there’s enough to link one of the greatest of modern myths with the village.

A more contemporary literary link with Heacham can be found in the wonderful poetry of Alan Brownjohn. Writing of a coastal walk where he strayed inland to the east from Heacham, Brownjohn observes that “each field and hedge looks green and living still, as I stride away” when “the whole long day is setting with that sun” (from the poem Sixteenth).

In the poem In the Visitors Book Brownjohn writes of the “exhausted, exalted coast” and notes the spring tide is “a cagey, persistent ripple towards us.” In January to April he once again visits the “cold plain stretch” at Heacham, and his later collections return to the quiet wildness of this stretch of coast:

There is only me in this landscape. There was only me

This morning, in the brightness of the beach…

Should I bow, in winter’s direction, like the grass?

- September Days

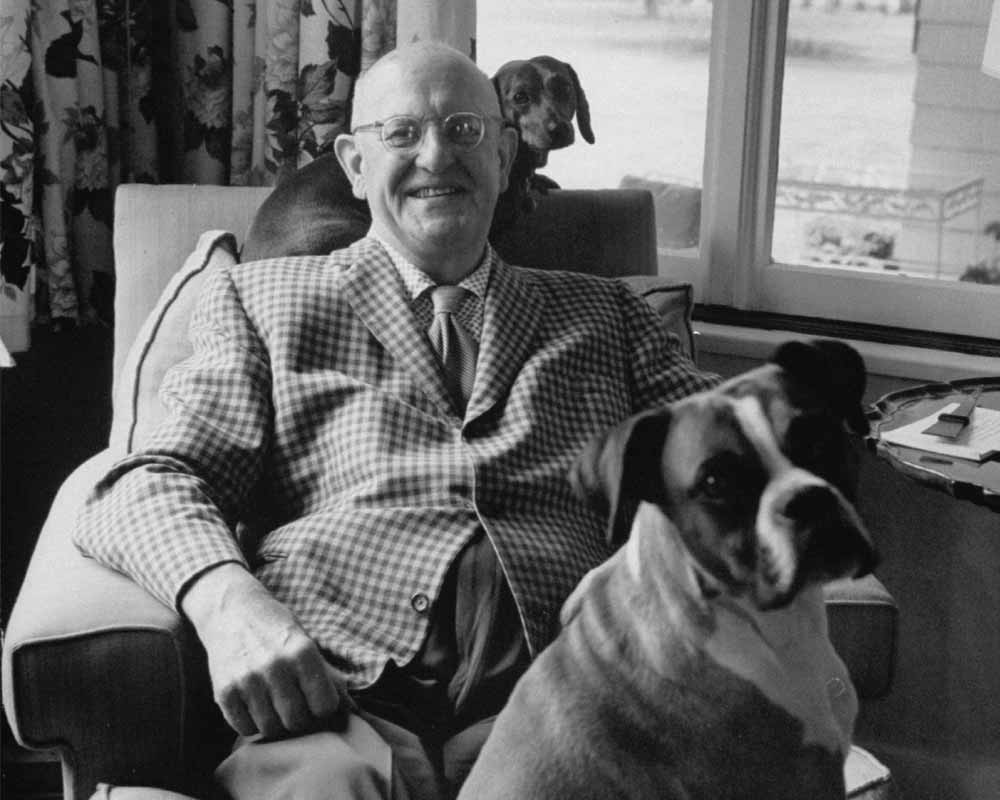

Moving further along the coast two of the most famous characters in English literature make their debuts in Hunstanton. PG Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster and Jeeves and their fictional home of Blandings Castle, complete with the park, lake, moat and estate of Hunstanton Hall make their first appearance in the 1915 short story Something Fresh.

Writing in his diary on 27th April 1929, Wodehouse clearly references the “frightfully bright” Hunstanton Hall, the butler with “the cheery soul who used to be the life and soul of the party” and in the same entry states that he “laid the scene for Money for Nothing (1928) at Hunstanton Hall.”

The village of Old Hunstanton is clearly identifiable in the moated hall, the stream with its little bridge and the path across the fields to the village.

Money for Nothing isn’t the only Wodehouse novel set in this part of Norfolk, and many of Wodehouse’s characters have Norfolk names, such as Lord Heacham and Jack Snettisham. Hunstanton features most significantly in Very Good Jeeves (1930) and A Pelican at Blandings (1969).

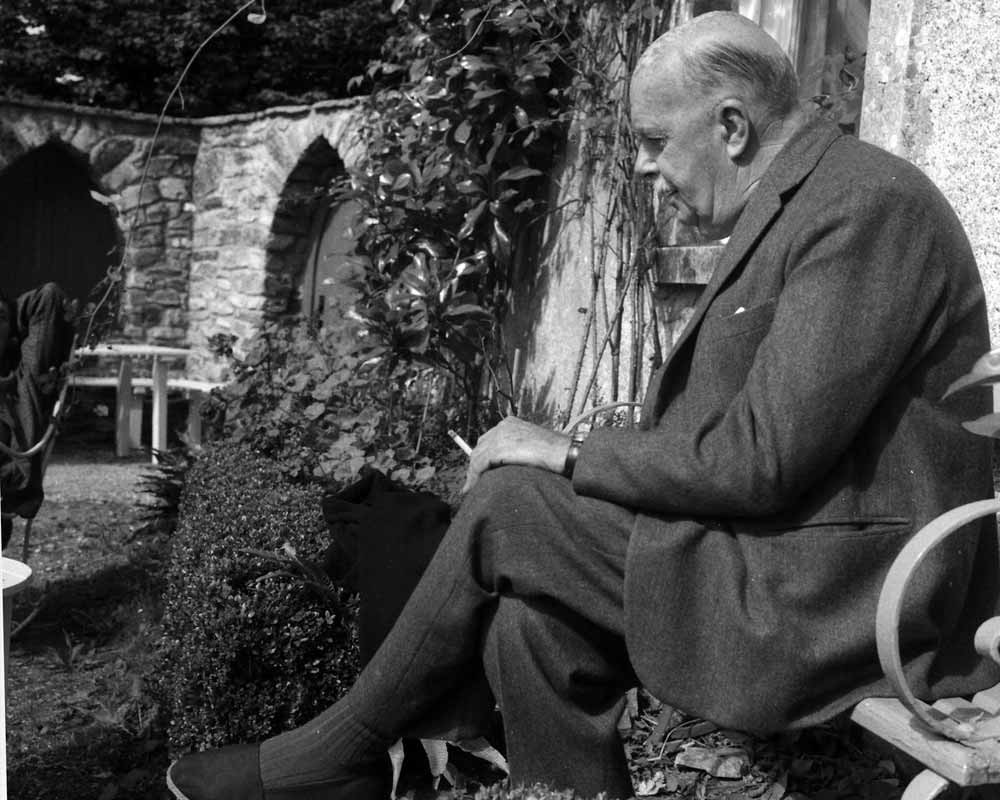

In LP Hartley’s The Shrimp and the Anemone Snettisham becomes Frontisham. At a family meal at the Swan Hotel (which must be the village’s famous Rose and Crown) the main protagonist Eustace is mesmerised by a view of the church.

“Within the massive framework of the grey wall seven slender tapers of stone soared upwards. After that, it was as though the tapers had been lit and two people, standing one on either side, had blown the flames together. Curving, straining, interlocked, they flung themselves against the retaining arch in an ecstasy - or should we say an agony? – of petrification. Pictures of saints and angels, red, blue, and yellow, pressed against and into him, bruising him, cutting him, spilling their colours over him.”

Hunstanton (Anchorstone in the Eustace and Hilda trilogy) provides the backdrop for another seminal moment in The Shrimp and the Anemone:

“Eustace gazed all about him...on his left was the sea, purposefully coming in; already its advance ripples were within a few yards of where they stood. Ahead lay long lines of breakers, sometimes four or five deep, riding in each other’s tracks towards the shore. On his right was the cliff, rust-red below, with the white band of chalk above and, just visible, the crazy line of hedgerow clinging to its edge.”

And it’s close to Hunstanton’s distinctive cliffs that the central motif of the entire trilogy occurs.

“Fastened to a boulder, just above the water-line was a shrimp and the anemone was eating it, sucking it in.”

The children cannot save the shrimp from its fate. It is also in Anchorstone in the final novel in the trilogy that Eustace and Hilda (with the “fastening” metaphor present again) the story reaches a more positive conclusion:

“The stability of paper-weights appealed to him. They tethered things down, they anchored the past. The Anchor Stone!”

These delightful coastal towns and villages are a joy to visit and a pleasure to live in but it’s clear they also have a very real literary sense of place.