A unique memorial to a lost generation

King’s Lynn Library is a beautiful building, but few people are aware of the fascinating and historically important inscriptions on its tower

On 18th May 1905, a kindly-looking gentleman in a tightly-buttoned frock coat ascended the steps of a new building on London Road in King’s Lynn and held aloft a small key.

“There are few doors which a golden key will not unlock,” he said, before officially opening the town’s new library and issuing its very first book.

That man was Andrew Carnegie, the Scottish-American businessman and philanthropist who gave away almost 90% of his vast fortune (worth around £3 billion in today’s terms) to various charities and foundations. One of his most famous and influential initiatives was the creation of what became known as ‘Carnegie Libraries’ which were built to provide a free service to all. King’s Lynn Library was a source of great civic pride, but ten years after Carnegie opened the building it was being used for a purpose he could never have envisaged.

The outbreak of the First World War in the summer of 1914 affected all people in all walks of life, and the life of King’s Lynn Library was no exception. At the time, the library (which had been judged by The Literary Yearbook as one of the best libraries using open access in the whole country) possessed 14,690 books, but started to see a drop in borrowings as members left for the front. Library staff had to suspend lectures and close the reading rooms due to lighting regulations, and although a Zeppelin raid over the town in January 1915 left the library intact, it was to have an enduring impact on the building.

Following the attack, the Berkshire Yeomanry (who were stationed in King’s Lynn at the time) received orders to use the library’s distinctive tower as an observation point to detect enemy aircraft activity. A telephone line was set up providing a direct line to the War Office, and the soldiers who manned the tower every night had to report in every hour.

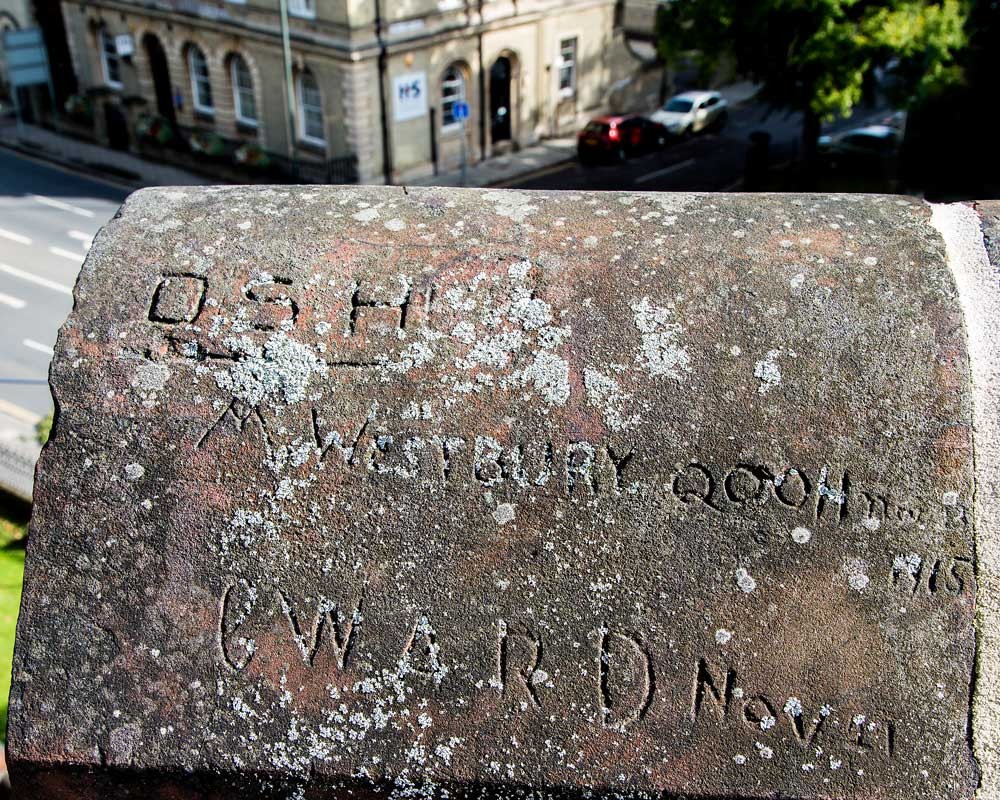

From then to the end of the war in 1918, the library tower was occupied by various territorial regiments and local volunteers. While there, the soldiers etched their names onto the brickwork, and some etched their regiment and service numbers. Now, with the help of regimental, yeomanry and military museums from Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Berkshire and Wales, King’s Lynn library staff have been able to trace the military records of some of these soldiers, revealing in many cases their sad fates.

“Tragically, out of the 30 or so names we’ve managed to trace so far, about two thirds were killed or badly injured,” says the library’s Kevin Hitchcock. “Hidden behind the fake battlements of the library’s tower lies a unique and tangible memorial to those men, and we’re hoping to record their histories and trace their descendants as much as possible – in fact, the tower has already been visited by one descendant!”

The Oxford, Bucks and Berks regiments were all mounted regiments stationed in Lynn between June 1915 and April 1916, using The Walks and Friars Field as camps where they kept their horses. The men were billeted in local homes, married local women, recruited local men and provided well-attended sports tournaments. More seriously, they were also required to provide men to be transferred to front-line regiments. Although the ‘men in the tower’ left little more than their names, they offer a fascinating glimpse into a terrible past.

Out of the 30 or so names we’ve managed to trace so far, about two thirds were killed or badly injured. Hidden behind the fake battlements of the library’s tower lies a unique and tangible memorial to those men

Take Maurice Pratt, No 2246 for example. The QOOH stands for Queens Own Oxfordshire Hussars, and Maurice was one of 200 men drafted into the Ox Buck’s Light Infantry (OBLI) and sent to France. They went over the top at the Somme in early October 1916, and Maurice was killed only a few days later – only recognisable by his uniform and the number 2246 marked on his boots.

Just above Maurice’s name is another QOOH transferred to the OBLI. A keen athlete who appeared in several newspapers of the time, A E Lovegrove was discharged from Army Service in 1917, suffering from severe frostbite he received while in the trenches.

Aubrey Cato would have had a good view of St Margarets when he made his triangular mark on the brickwork. Just a few months later in October 1916 he and his comrades were heading to the forward trenches, where they were hit by artillery. Aubrey was killed instantly and has no known grave.

R.G Wiseman was a member of the Royal Buckinghamshire Hussars (RBH). Many of the RBH were transferred and served in the Middle East, but in July 1918 they were transferred to the Machine Gun Corps. Sadly, Reginald was killed in action only two weeks before the end of the war.

J Young RDC is an interesting inscription – the RDC stands for Royal Defense Corps, which was the First World War’s equivalent of the 'Dad’s Army' of the Second World War. These men were local and were perhaps veterans of previous conflicts.

In addition, some men from King’s Lynn joined the regiments. The inscription "A Burn" was made by Arden Burn of Gaywood, who went to King Edward VII School. He was another soldier who joined the QOOH before being transferred to the OBLI and ending up at the Somme in early October 1916. He was badly injured and spent nine months in hospital. Arden was one of the few who survived – and after the war ran a nursery on the Wootton Road. Although it is possible to visit the tower, it does require climbing ladders and climbing through hatches – and an appointment is necessary. Note that it’s best to visit in the summer months when the etchings are more visible.