Mayhem in the Fens

Fuelled by anger and alcohol, the Littleport riots of 1816 are widely regarded as some of the most furious uprisings in the history of East Anglia. Russell Lyon details these brutal conflicts and their consequences...

When visiting family living in the Australian city of Brisbane, I occasionally have a morning coffee overlooking Moreton Bay and the Island of St Helena - which was once a penal colony. Casting my mind back to East Anglian history, I often wondered if anyone involved in the infamous Littleport riots was imprisoned there. However, a visit to the local library soon put me right. It was not open for business until 1826, ten years too late.

The violent fenland riots and their brutal aftermath left a permanent mark on the history of what was widely considered to be a quiet rural region.

Peace had returned to Europe after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, but misery and hunger were too often the price paid for war and the agricultural poor of England suffered badly.

War veterans came home after being discharged to find food was scarce and work was even scarcer. Even if you could find a job, the wages were hardly above starvation level and many families faced severe malnutrition. Agricultural pay was only 8-9 shillings a week, the cost of flour and bread doubled inside a year in 1816 and meat was almost unobtainable - well beyond the pocket of the average farm worker.

Although many farmers and landlords were under financial pressure and could not pay their own rent, some were aware of the suffering in the countryside. They did their best to alleviate the common distress among their working families by giving free milk, free rabbits, firewood and peat to many. However, the situation got so bad that ‘desperate men were driven to desperate deeds’ and economic depression swept the land as bad as any plague.

Robbery with violence was a capital offence and almost everyone detained by the authorities could be hung...

By 1816 the situation in Littleport exploded into mayhem. Between 50 and 60 men were present in the Globe Inn on what was known as a ‘club night.’ Each man was entitled to a quart of beer and the talk soon turned to Henry Martin. He was a local farmer and politician, too fond of his own mouth, with no sympathy for the needs of starving people. In short, he was a bully and a coward and a mob gathered outside the pub determined on trouble.

Stones were collected, windows broken and properties vandalised. The vicarage was among the first on the list and, when the mob arrived, the Vicar stood with a loaded pistol and threatened to shoot the first man to enter. They ignored him (and of course he didn’t) and they rampaged through the house stealing and breaking furniture. They moved on from there vowing to kill Henry Martin, but he knew they were coming for him and bolted out the back door. However, there was no stopping the drunken mob now. Their numbers had swollen into the hundreds and they charged through the town, smashing, stealing and drinking from barrels of beer. Cool heads tried to calm the insurgents by reading the Riot Act, which warned that any being caught by the authorities would be subject to the most severe penalties, but it had little effect.

When they had all but finished causing havoc in Littleport, the thoughts of the pack of brigands moved to Ely. The leaders commandeered a wagon pulled by four black Fen horses and armed it with four punt guns pointing forward. More than 100 rioters followed, armed with guns, bludgeons, eel spears and bill hooks. There they were met by a gang of Ely roughs and created absolute mayhem in the town.

By now authorities were alarmed and alerted following a wild ride to Bury St Edmunds by Thomas Archer, a young lawyer from Ely. Major Purvis, the officer in command at Bury, called out a troop of Dragoon guards. There were only 16 of them, but they were all veterans of Waterloo. Major Purvis listened to Thomas Archer and laughed. “Last year we were in the Battle of Waterloo and now we are going to fight the Battle of Hullabaloo.”

By late afternoon most of the troublemakers in Ely were sobering up and had retreated back to Littleport. The Dragoons rode to Ely, staying overnight, and the next day advanced to Littleport. The main body of the rioters had retired to the George and Dragon and refused to come out. This was soon rectified by a fusillade of shots fired through the windows of the public house. In the melee a Thomas Sindall tried to steal a carbine from a trooper and was shot dead, becoming the only fatality of the whole affair.

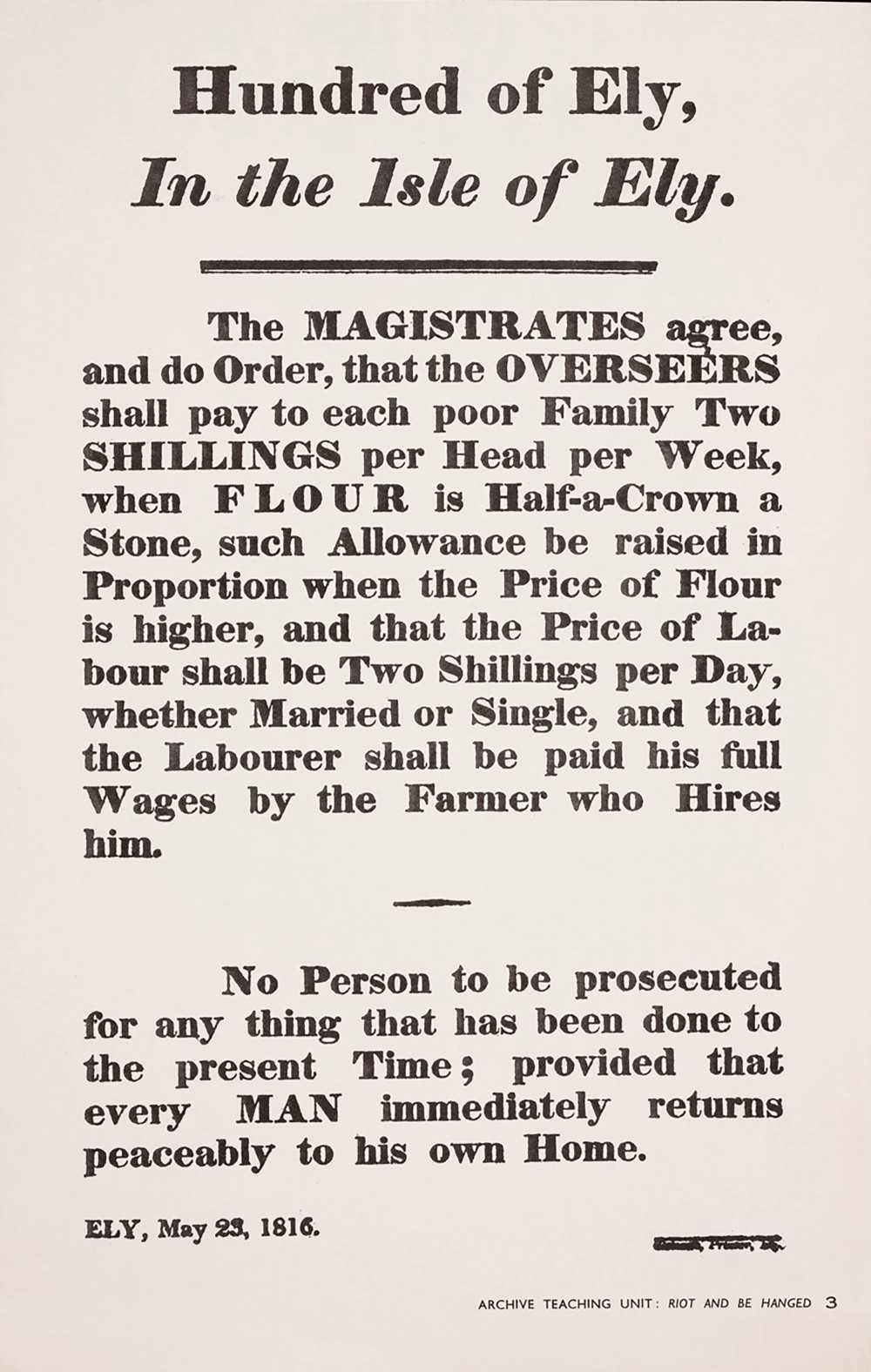

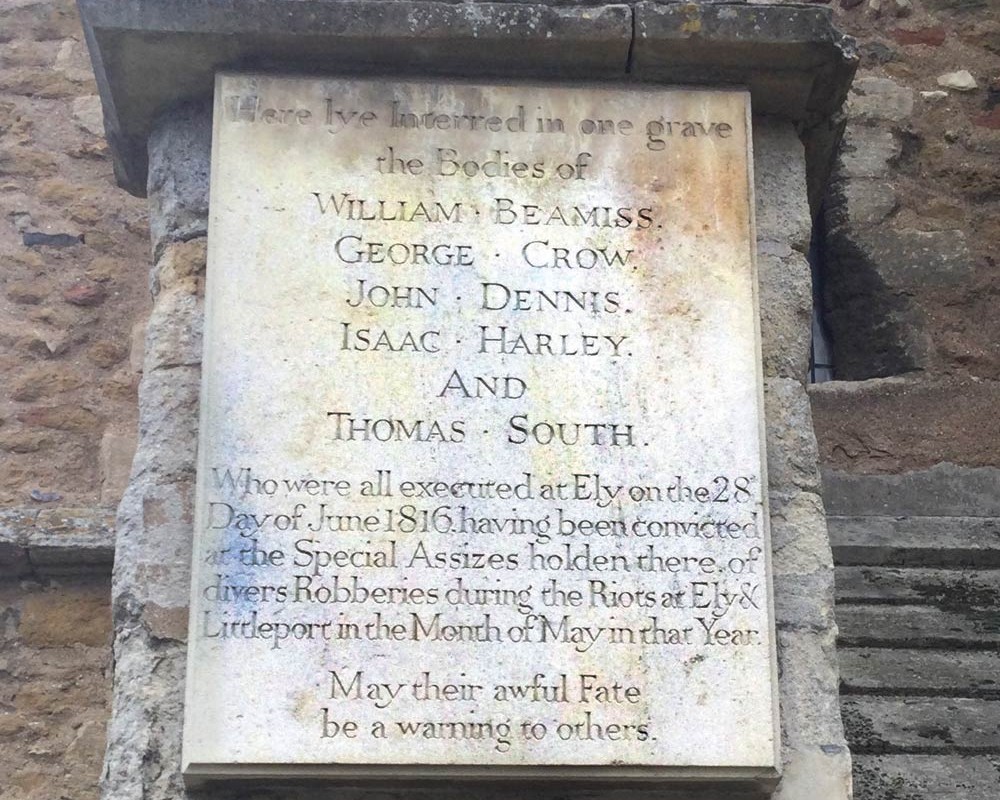

ABOVE: A painting by Thomas Rowlandson which resembles a market square similar to Ely’s, where the 1st The Royal Dragoons paraded on 24 May 1816. Proclamation by the magistrates of Ely to the rioters in attempt to put an end to the unrest. BELOW: A memorial plaque recognising the five Ely and Littleport rioters who were executed on 28th June 1816 located on the south wall of the west tower of St. Mary’s Church in Ely. You can visit the gaol cell at Ely Museum, where convicts were imprisoned during the time of the riots. © Matthew Smith Architectural Photography & Ely Museum.

The authorities, now with the backing of the local militia as well as the Dragoons, started the process of rounding up the miscreants. Up to 80 wanted men were found and arrested and various articles of plate and silver were also recovered. On June 17th, Magistrates from Cambridge arrived in Ely and the trials began. No account was taken of the hardships and hunger which had led to the uprising. Judicial history at that time was ruthless. Robbery with violence was a capital offence and almost everyone detained by the authorities could be hung. On June 22nd, 24 men were condemned to death. There was uproar in the court when the sentences were handed down and it took the Judge to threaten to condemn a few more before order was restored.

In the end only five men were executed. The rest were imprisoned in Ely jail for a year (commuted) and the remainder were transported to Australia. The five condemned men were executed on June 28th and taken to the gallows in a horse-drawn cart sitting on their own, soon to be occupied, coffins.

The prisoners for transportation were removed to Newgate prison in chains and shortly afterwards sailed to Botany Bay Australia. They all survived the hazardous 10,000-mile voyage on the sailing ship the Sir William Benley to arrive on 9th October. Afterwards their fate was mostly unrecorded. A Richard Rutter is known to have died aged 51 in 1827, having been killed with a spear in Tasmania by a native Aboriginal. Joseph Easey resumed life as a farm worker in New South Wales after serving his sentence and died aged 77, and James Newell died aged 39 in 1834 without returning to England. The others to survive their sentences may have returned home to Littleport, but that was by no means certain as conditions in the camps were very severe.