Looking back at lost King’s Lynn...

In his forthcoming book, local historian Dr Paul Richards looks at how Lynn has changed over the centuries - from the coming of the railways to the arrival of a retail revolution

Lynn has a history going all the way back to the 11th century, but change and continuity always go together and the last 150 years of the town’s story have been of particular significance.

Lynn’s maritime economy and society, dependent for centuries on its great river, was being eclipsed by the 1870s and 1880s. Factories associated with the new enclosed docks linked to the national railway network heralded Lynn’s first industrial revolution. It had profound consequences for what was a traditional English port and market town.

Fisher’s End (today’s North End) lost its ancient harbour to the first dock, which attracted modern steamships engaged in overseas trade; and the fisherfolk with their wooden sailing boats co-existed with this new world.

Railways robbed Lynn of most of its coastal shipping from the 1840s and iron steamships were rapidly replacing wooden sailing vessels by the 1880s. Visitors had once been impressed with Lynn’s river or harbour which was a forest of masts as multitudes of mariners frequented the local taverns. Their customer base shrank as the sailing ships disappeared.

Such licensed premises had been the hubs of Lynn’s maritime community acting as job centres, lodging houses and entertainment venues. Many closed in the riverside streets in the years before 1914 - King Street, Queen Street and Nelson Street had been the location of numerous pubs.

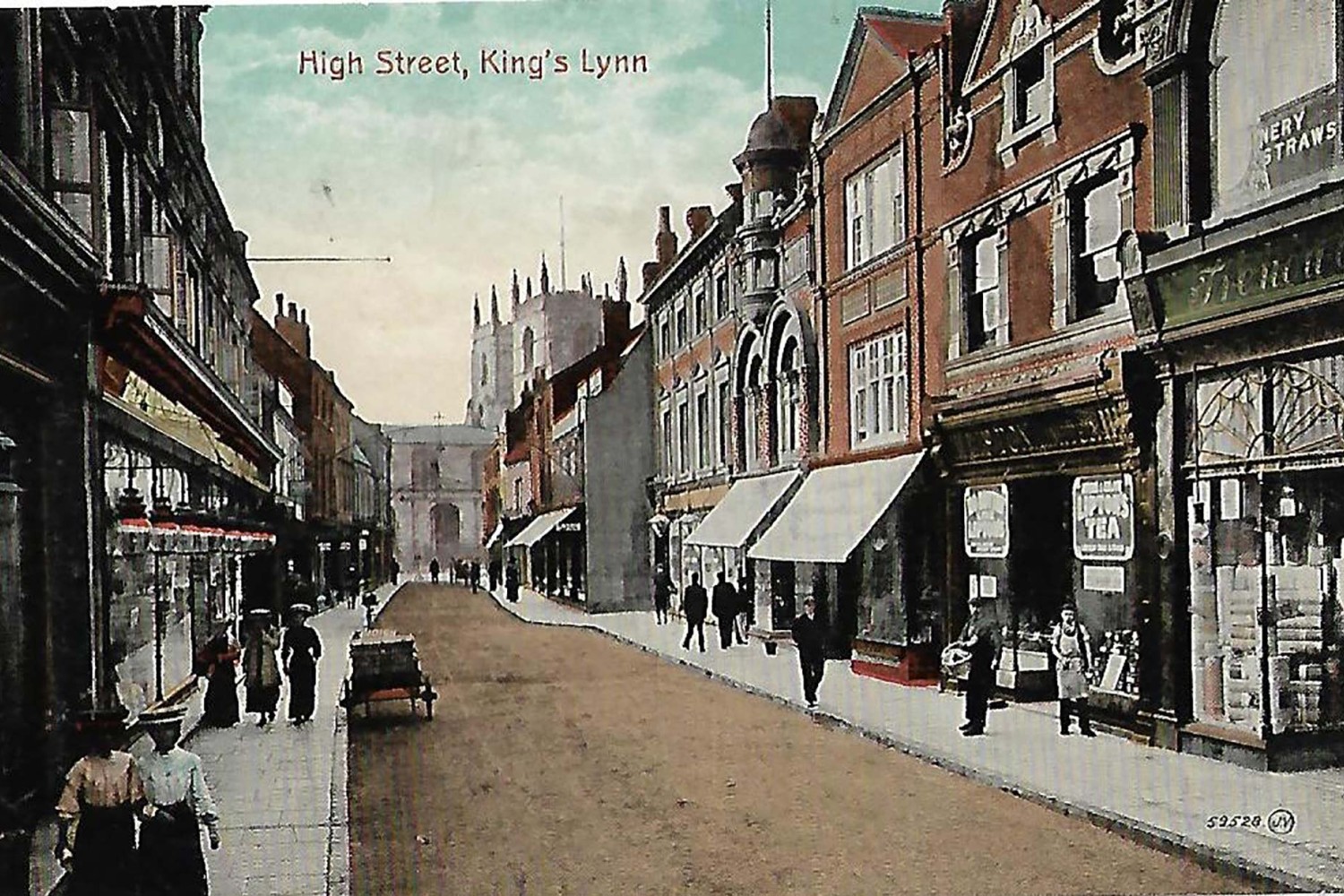

At the same time the principal shopping streets in England’s major towns were undergoing a retail revolution (1870-1914) as department stores were built to serve a growing consumer society. Lynn was no exception with the onset of modest but significant industrialisation.

The High Street began to change its character as big stores replaced smaller shops, and it was a Norfolk man who opened the first department store in 1872. This was Alfred Jermyn, whose business was acquired by Debenhams in 1943 and sadly closed in 2020.

Before 1914 big city firms investing in nationwide chain stores were also establishing outlets in Lynn where they were to erect much larger premises later in the 20th century.

Perhaps the best example is Marks & Spencer, whose fledgling firm opened a small bazaar in the town in 1910 - it was rebuilt as a much grander store in 1932

State intervention in the health and housing of English townspeople was accelerated by the growth of democracy in Queen Victoria’s reign and there was a mass electorate by 1918. Social reform rose to the top of the political agenda for local and central governments.

A high percentage of Lynn’s labouring population was concentrated in insanitary courts or yards off the main streets - and Norfolk Street had more than any other. Neglected and overcrowded yards faced increasing public scrutiny from the 1880s when the housing of the working classes became the subject of parliamentary legislation, but it wasn’t until the 1930s that they were being demolished. New council housing estates were developed on Lynn’s outskirts to rehouse the displaced population.

For centuries Lynn’s industries were clustered around four small fleets or rivers which traversed the town and emptied into the Great Ouse and the new Fisherfleet excavated in 1868 retains its original function to this day. In South Lynn the Friars Fleet was the location of shipbuilding yards and the whaling fleet, although both had disappeared by 1870.

The banks of the Millfleet and Purfleet were hugged by breweries and granaries as well as the tenements of the working classes. These two fleets were regarded by the local authority as the town’s greatest health hazards by 1870, but improvement schemes were delayed by public affection for these ancient waterways. Typhus epidemics finally jogged the Council into action in the 1890s.

However, all this Victorian and Edwardian economic growth wasn’t sustained and in 1945 the council searched for a much-needed pathway to regenerate Lynn. Its population ‘grew’ from 20,000 in 1900 to a mere 25,000 in 1950. The solution was an ‘overspill’ agreement with the Greater London Council (GLC) in 1962 whereby manufacturing firms and newcomers would settle in the Norfolk town. This was tantamount to a second industrial revolution which was to be even more transforming than the first.

Though new housing and industrial estates were built on Lynn’s outskirts, parts of the historic town were redeveloped in the 1960s and 1970s for big shops and car parks. Some ancient buildings were lost, and the removal of the cattle market to the town’s edge in 1971 to make way for a new bus station and a supermarket emphasised the break with the past.

Lynn was no longer the old world country town ideal for a quiet weekend as advertised by magazines in the 1950s.

Happily, Lynn retains an impressive historic built environment to connect us with what was for centuries a premier English seaport and market town, with the exceptional riverside streets and the two market places, but its identity has been remade over the last 150 years.

Lost King’s Lynn by Dr Paul Richards will be published by Amberley in September 2021.