The idyllic stream harbouring an intriguing history

Shedding light on a project of passion to revive the remnants of Narborough’s long lost bone mill

While its crystal-clear waters and lush banks offer a sanctuary for wildlife and wonderful walks, there is one isolated stretch of the scenic River Nar that harbours a grisly past.

Overlooked by colourful kingfishers, elegant swans, water voles and dazzling dragonflies lie the remains of a 19th century water-powered mill. This historic site represents the last vestige of an industry that produced fertiliser from ground bones to enrich the nearby farmland.

From around 1830, the mill was owned by the Marriott Brothers, who also built the Narborough Maltings and controlled navigation rights. In its heyday, from 1838 until almost the turn of the century, the site was bustling with horses hauling barges loaded with bones from farms, slaughterhouses, the whaling industry, and (somewhat more grimly) from cemeteries in northern Germany. The giant water wheel drove machinery that processed the cargo into bonemeal, which local farmers collected by the sackful.

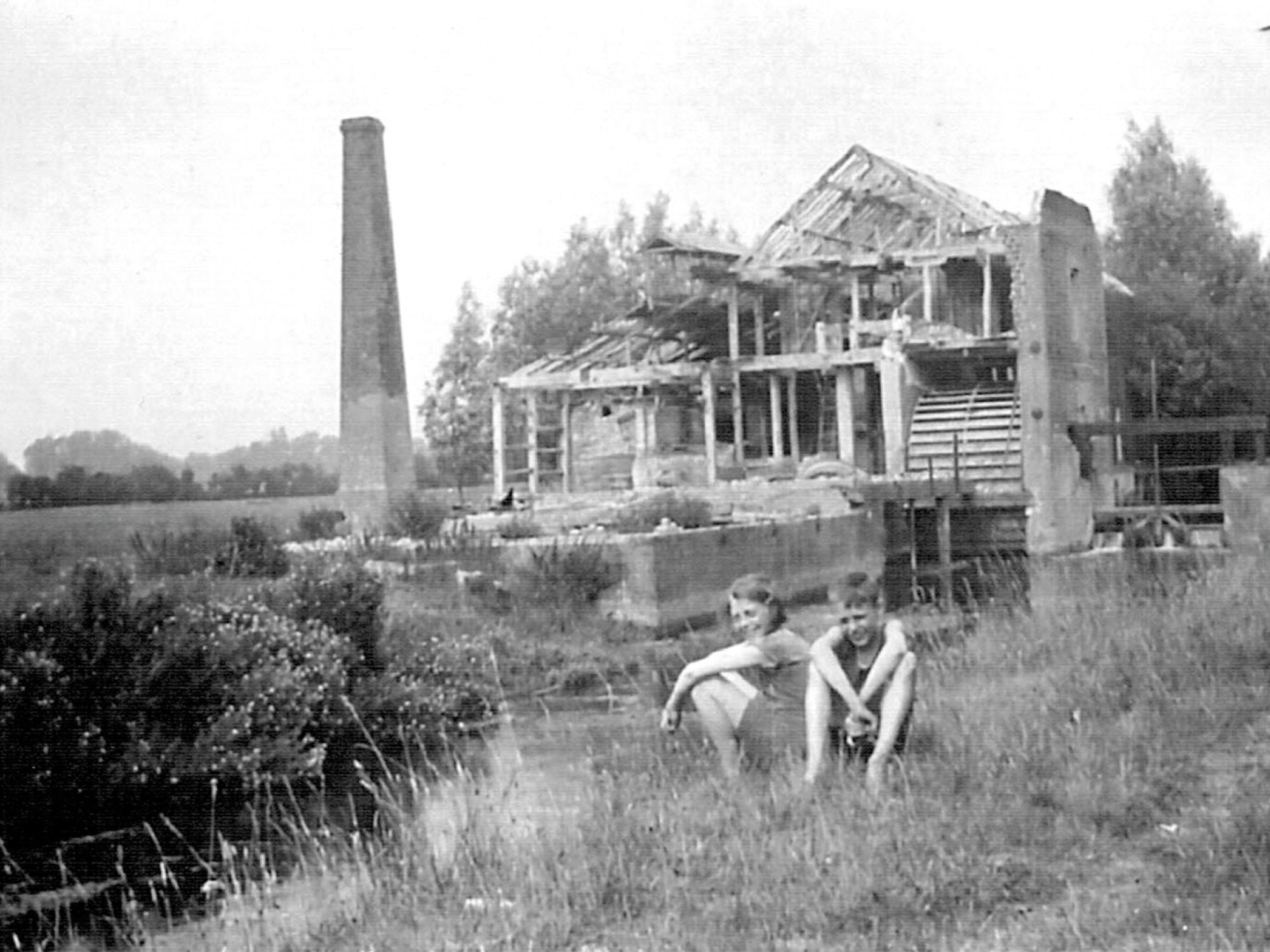

The arrival of faster and cheaper rail transport, increasing debts, and the diversion of this section of the Nar led to the industry’s collapse. The mill building was gradually dismantled, most of its machinery was scrapped, and the site was left to decay, becoming little more

than a forbidden playground for local children.

It was the discovery of the abandoned waterwheel, overgrown with brambles and filled to the axles with soil, that inspired the present owners of the site and a group of dedicated volunteers to explore its enthralling 120-year-old history.

In the 1970s, Robin and Beryl Munford purchased The Maltings at Narborough, including a segment of riverbank. They were fascinated by the 16-foot diameter wheel spanning part of the watercourse about a mile upstream and it became Robin’s dream to see it turn again. After he sadly passed in 2013 without watching this wish come true, his wife, daughters Emma and Elaine and son Fred pledged to restore the site in his memory. In 2015, they obtained a £92,000 Heritage Lottery grant to hire skilled craftsmen who worked alongside a team of dedicated volunteers. Together, they spent countless hours meticulously unearthing lost treasures and breathing life back into the site.

“My father would have loved to see the wheel working again,” Emma remarks. “He’d have taken immense pride in our achievements, and we derive great satisfaction from sharing the mill’s history with others. It’s astonishing how many locals, including those living in the village, were unaware of this fascinating gem on their doorstep.”

The restoration journey has been an extraordinary experience of discovery for both the family and the volunteers. They revealed the brick flooring of the main building, the principal wall and pier, two sets of millstones, and remnants of the blacksmith’s shop (including the forge and anvil stand),

as well as an elevator and underground sluices.

The team has made many more discoveries over the years, including tools, machinery fragments, clay pipes, broken bottles, and even a portion of a human skull dating back to the mid-13th century. This find supports rumours that bones unearthed from Hamburg’s graveyards made their way to the mill for grinding.

Lead volunteer Graham Bartlett vividly remembers the excitement of seeing the waterwheel turn again in October 2015, after more than a century of dormancy. “We celebrated with cake and drinks in an event to mark the end of months of restoration by excellent craftsmen, who replaced irreparable parts of the wheel,” he recalls. “Some sections were still in remarkably good condition, despite long exposure to the elements, and served as models for restoring the rusted parts.”

Alongside repairs to the brickwork, this soaked up much of the funding, leaving Graham and his fellow enthusiasts to continue the excavation work. They have since created a welcoming visitor centre which echoes the outline of the original mill, established a restored railway carriage as their base and received Unsung Heroes Awards from Breckland Council for their amazing efforts.

Further grants enabled them to enhance the natural beauty of the surroundings by creating a wildflower garden with bird boxes, kingfisher tunnels and insect hotels.

“There have been so many exciting discoveries made since we began but, unfortunately, no records have emerged to shed light on the mill workers,” says Graham. “We’d love to uncover details like their numbers, wages, and working conditions; it’s a challenge but there is always hope!”

As the site is situated on private property, public access is limited to Heritage Open Days in September, Mills’ Weekend in May, or pre-arranged visits. However, one can catch a view from the Nar Valley Way, which runs along the opposite bank of the stream. Additional information about the mill’s history and its restoration can be found at www.bonemill.org.uk