What was normal for Norfolk in WWII

Culturally, geographically, artistically and politically Europe is still defined by the Second World War, but what impact did the conflict have on the traditionally tranquil and peaceful county of Norfolk?

Although the Second World War had an enormous impact on the entire country, Norfolk has a unique place in the domestic history of the conflict and can claim a number of remarkable firsts.

The Royal Norfolk Regiment’s 2nd Battalion was the first complete infantry unit of the BEF to land in France at the start of the war, and two of its members (Cpt Peter Barclay and Cpl Mick Davis) were the first British soldiers to be decorated for their actions.

Rather fittingly, a few years later the first soldiers ashore the Normandy beaches on D-Day were men from the Royal Norfolks - and the first attack on Berlin at the end of the war in Europe was by planes from RAF Marham. The first man on occupied Japanese soil (Lt Colin Chapman) was from Norwich.

The Royal Norfolk Regiment was awarded more Victoria Crosses (five in total) than any other county-based regiment in Britain during WWII, and a pigeon bred and trained at Sandringham in the royal pigeon loft became the first in the whole of Europe to successfully deliver a message from a force-landed aircrew. Released in Holland on 10th October 1940 at 7.20am, ‘Royal Blue’ delivered his vital message to Sandringham four hours and ten minutes later - and earned the Dickin Medal for his work.

Even more remarkably, very few people know that the iconic Battle of Britain actually started in the skies of Norfolk. Early on the morning of 10th July 1940 (4.40am to be precise) three Spitfires from No.66 Squadron took off from RAF Coltishall - and shortly came under attack from a German Dornier bomber, which swiftly forced one of the Spitfires back to base. The other two pursued the bomber and shot it down over the sea - and the ensuing battle would last until the end of October before helping define our national character for the rest of the 20th century.

Although its proximity to Europe meant that Norfolk was well prepared for the arrival of any enemy force (it would take until the 1970s for all the landmines on the beach at Trimingham to be cleared) it did experience an invasion of another kind.

Two days before the Second World War was officially declared (Friday 1st September 1939) hundreds of young children started arriving in the county, destined for ‘dispersal centres’ (local schools) and given a quick health check and a bag of rations. The fact the authorities had stockpiled 976 cases of tinned milk, 21,000lbs of biscuits, 73,000 cases of chocolates and 21,000 carrier bags may seem rather excessive, but within three days the number of young children in Norfolk had risen by over 21,000.

One evacuated youngster called Maurice Micklewhite from Southwark in south London eventually found himself living with a family on a farm at North Runcton, a few miles from King’s Lynn. The young boy took part in the annual village pantomime playing Baron Fitznoodle (the father of the ugly sisters) in Cinderella and took to it like a natural. Some 80 years, 160 films, three Golden Globes and two Oscars later he’s better known to us as Sir Michael Caine CBE.

At home, war affected virtually every walk of life.

People listened to BBC radio programmes such as ‘Can You Hear Me, Mother?’ and ‘It’s That Man Again’ (there were no local radio stations at the time) and in the absence of lavishly-produced films the Majestic Cinema in King’s Lynn was showing government-issue features such as ‘Fuel Flashes’ and ‘The Kitchen Front’.

People wishing to eat out would visit their nearest British Kitchen (it was officially a ‘communal feeding centre’ but the government thought that sounded too much like something the Soviet Union would do) where you could treat yourself to a bowl of soup for 1p.

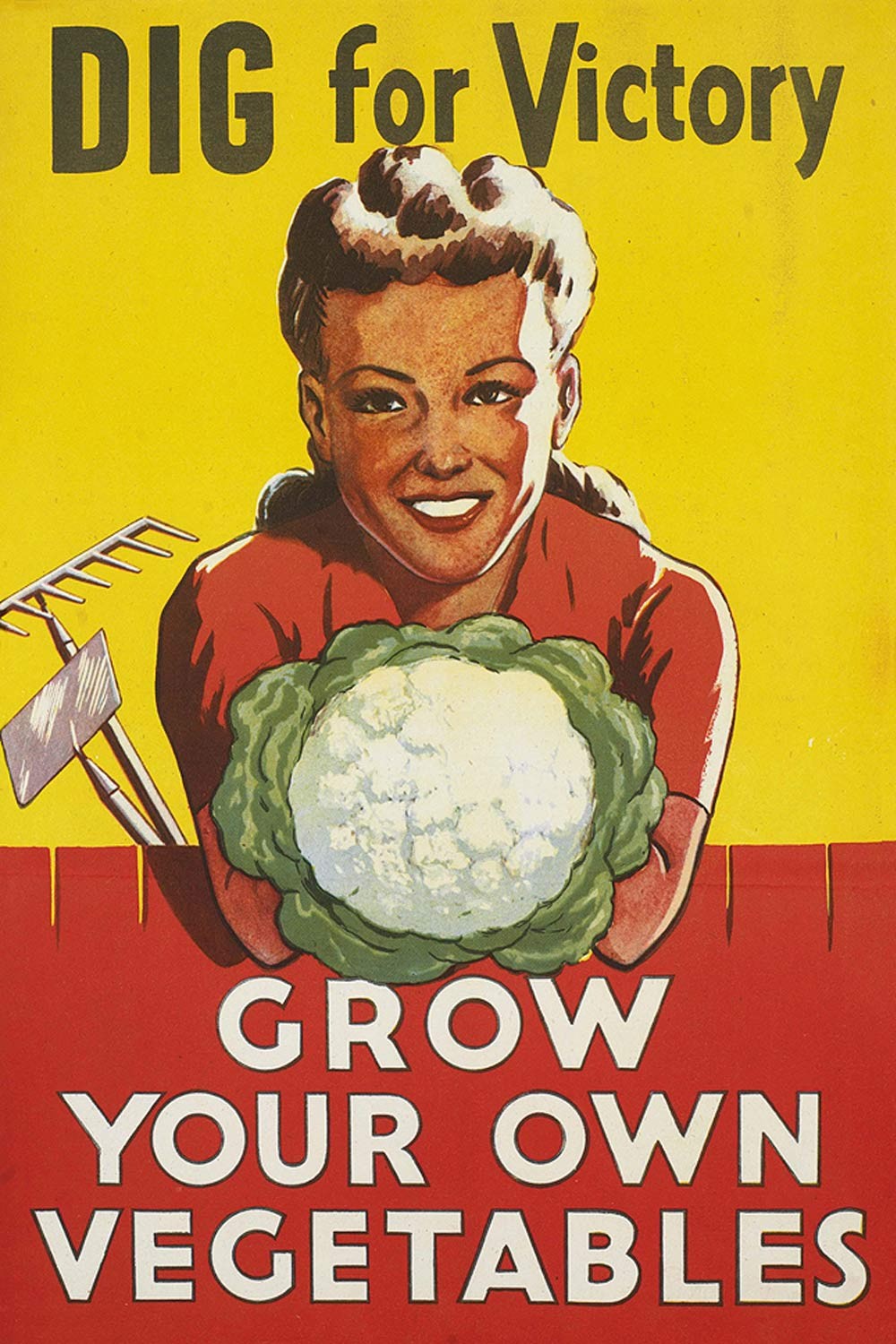

Along with the rest of the country, Norfolk experienced severe food shortages during the Second World War, although we now know that the introduction of rationing and increased reliance on home-grown vegetables led to greater health among the general population.

Despite the rather frugal fayre on offer from your (and your neighbours’) garden, the food star of the war was the meat-free and vegetable-packed Lord Woolton Pie. Named after the government’s Minister of Food in the early 1940s, it was actually created at the Savoy Hotel in London by the Maître Chef de Cuisine, François Latry.

He suggested substituting the vegetables according to whatever was available at the time (the Norfolk version was heavy on peas since crops reached record levels towards the end of the war) but the essential recipe was as follows if you like a genuine taste of the 1940s:

Happily, there was some good news on the food front at home. The ban on visiting the seaside was lifted in the summer of 1944, and trains and buses flooded into Great Yarmouth, Hunstanton and Cromer as people travelled from miles away to enjoy an ice cream on the Norfolk coast. The government’s Minister for Food John Llewellen actually allowed supplies to be made available for its manufacture.

That’s surely the definition of what’s ‘Normal for Norfolk’ - irresistible food in a beautiful location during the most difficult of circumstances. And we can all identify with that.