Blessed by nature. Made by man.

The Broads National Park is one of Norfolk’s genuine treasures and is enjoyed by millions of holidaymakers and nature lovers from around the world - but its origins are surprisingly mundane...

It’s difficult to avoid superlatives when talking about the Norfolk Broads. Home to little more than 6,000 people they attract almost 8 million visitors a year, who bring some £450 million into the local economy. Comprising 117 square miles, seven rivers, 13 scheduled monuments, 125 miles of navigable waterways and 63 broads (most of which are less than 15ft deep) the area is Britain’s largest protected wetland and is a safe haven for 25% of the country’s rarest species. The Norfolk Broads contains 28 Sites of Special Scientific Interest, and is the only place you’ll ever see the iconic Swallowtail butterfly.

A young man called Horatio Nelson learned to sail here, David Bowie mentioned it in his classic song Life on Mars, and it helped local boatyard owner and radio engineer Christopher Cockerell to invent the hovercraft.

Breathtakingly beautiful throughout the year whether you’re walking, sailing or simply enjoying a good meal, you might think this is one of our most precious natural wonderlands.

But you’d be wrong, because despite the picture-postcard environment, abundant wildlife, magnificent birds and rare plants, the Norfolk Broads aren’t natural at all.

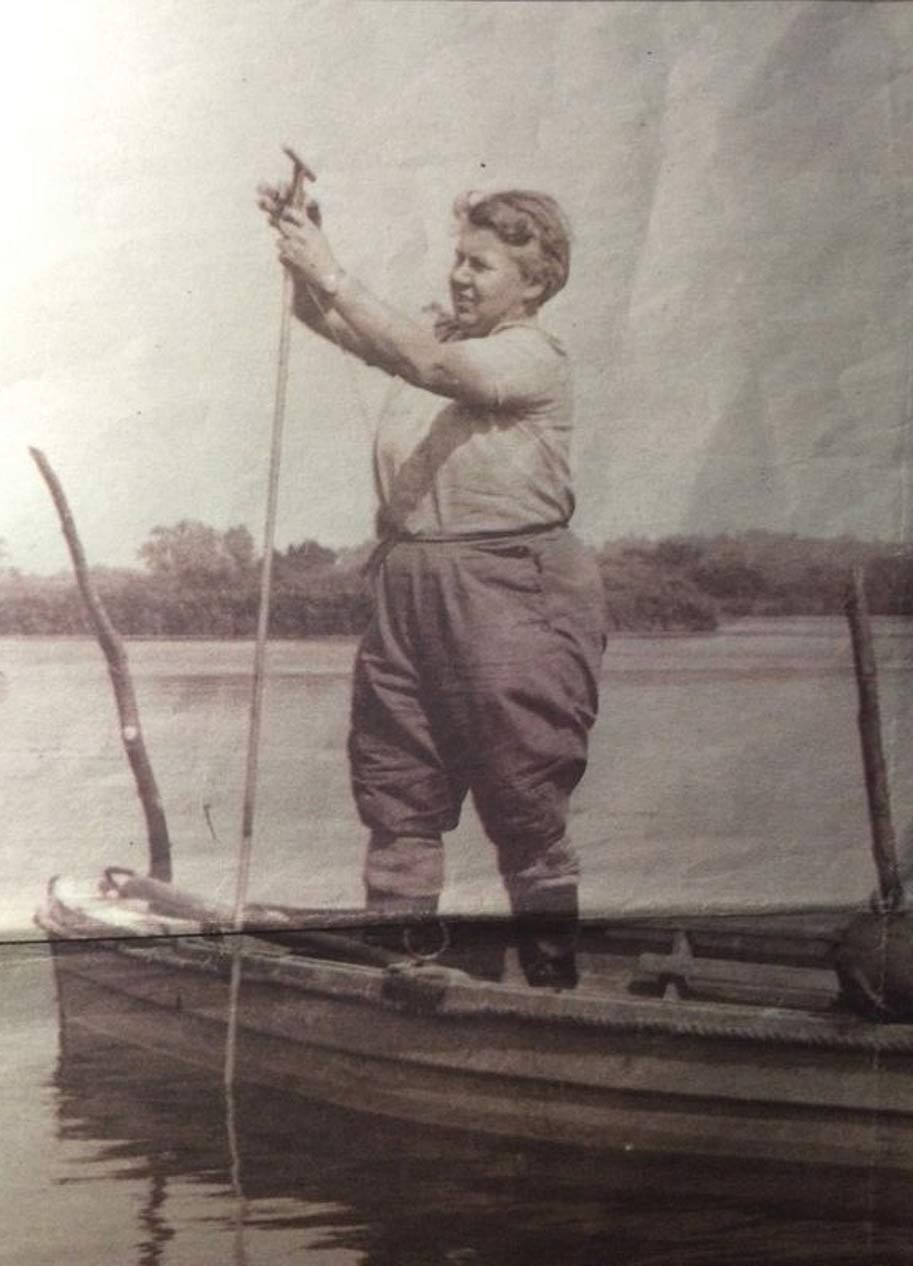

In the Royal Geographical Society memoir The Making of the Broads published in 1960 a woman called Joyce Lambert proved what several people had suspected all along - that the Norfolk Broads were man-made. In fact, they were an industrial by product.

Almost 1,000 years ago the eastern part of Norfolk was one of the most densely-populated parts of the country, and the population needed two things - somewhere to live and some way of keeping warm. Once all the native woodland had been chopped down, another source of fuel was desperately needed (energy crises are nothing new) and it didn’t involve looking to the sky. It was directly underfoot.

Over the next 200 years, an estimated 900 million cubic feet of peat was extracted from the ground (Norwich Cathedral itself burned its way through half a million blocks of the stuff a year), and the excavations were often almost 10ft deep.

But as we’re now only too aware, the idea of taking extremely carbon-rich and slow-forming material out of the ground and burning it isn’t the greatest idea in the world. And in an area as famously flat as Norfolk, the inevitable happened. Due to frequent flooding and rising sea levels the massive holes gradually filled with water and joined the surrounding rivers, making peat extraction impossible.

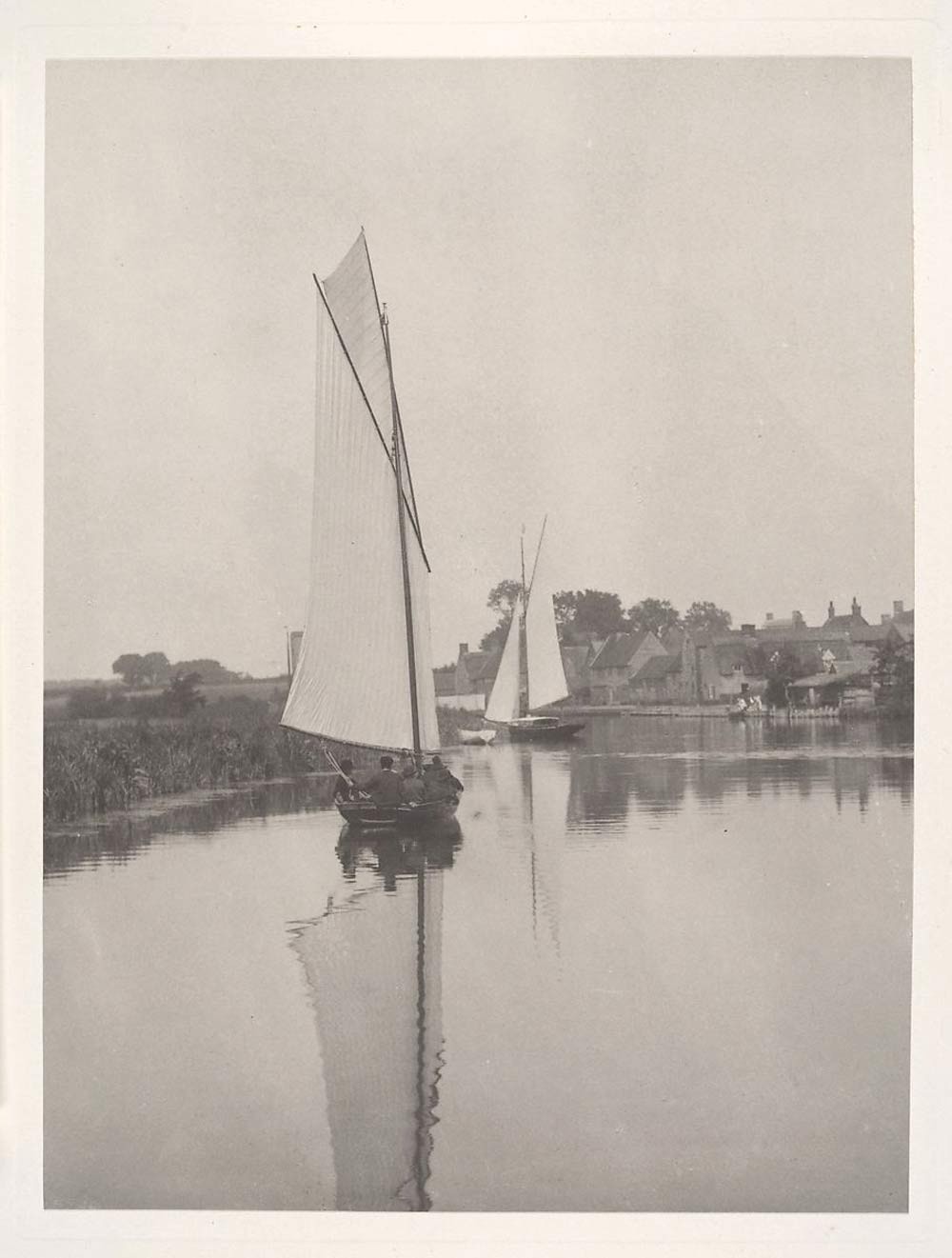

This was a cloud with a silver lining however, at a time when Norwich was the biggest city in the country after London. The newly-created waterways were ideal for exporting wool, woven products and agricultural produce, and gave rise to the dominance of the iconic Norfolk Wherry, which could carry around 25 tons and would be in service for the next 200 years.

At one time there was some 300 wherries on the Norfolk Broads, but only eight are thought to have survived to this day. Thanks to the work of the Norfolk Wherry Trust, it’s still possible to see some of these wonderful boats, and their lovingly-restored Albion is the only original commercial wherry available to hire - a boat trip that was judged one of the best in the UK by BBC Countryfile.

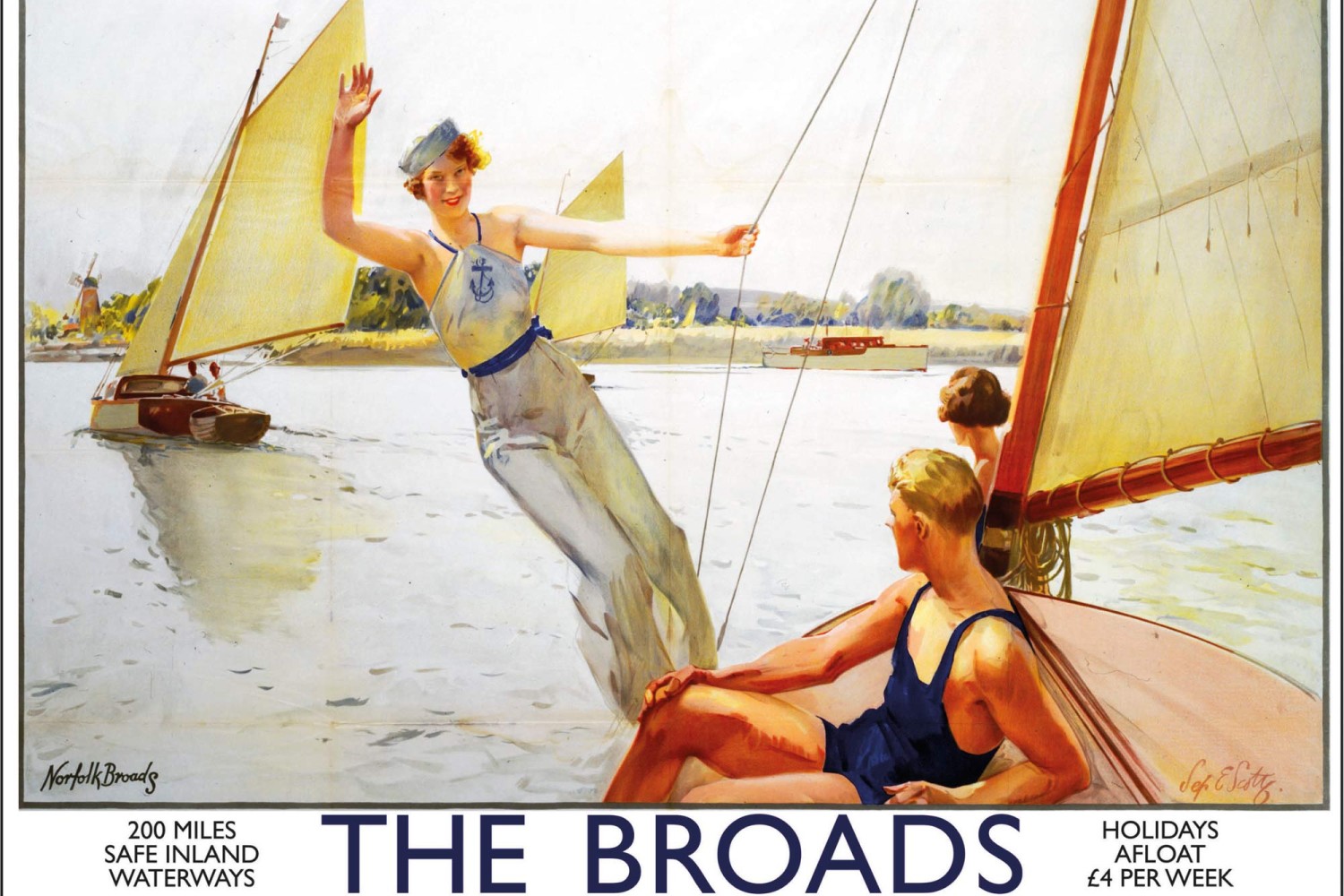

When Norwich was linked to London by the railway in 1845 (followed by King’s Lynn the following year) it opened the area to the entire country and ushered in the growth of a thriving tourism industry. After local boatbuilder John Loynes started a boat hire business in Wroxham towards the end of the 1870s, offering craft with “every convenience for cooking and sleeping” the Broads would never be the same again.

Holidaymakers flocked to the area, lavish regattas were held, and competitive yacht owners raced across the waters until world events put everything on hold.

In 1913 the army started preparing Hickling Broad as a base for the anticipated war (it was never used) and in 1918 the Broads was commandeered under the Defence of the Realm Act. It was even more affected by the outbreak of the Second World War, as the government judged the area a prime target for any invasion. Boatyards stopped working on luxury boats and began building military vessels, and boats of all types (including the remaining wherries) were moored in open water to create blockades and prevent seaplanes landing.

Restrictions on visiting the Norfolk Broads were lifted in 1943, but the effects of conscription, rationing and war damage meant the area took almost two decades to recover. Helped by advances in engine technology, improvements in design, and the development of new lightweight materials such as plastic and fibreglass the Broads grew to become one of the most popular holiday destinations in the UK.

Its transformation from industrial site to spectacular environment was officially recognised in 2015, when the Broads became the country’s 15th National Park, highlighting its unique biodiversity, precious wildlife, and its cultural and historical significance.

The passion for boating holidays in Norfolk continues to grow, alongside an increased interest in wooden boat restorations, the preservation of local history and environmental issues - all of which can be explored at the Museum of the Broads in Stalham, which also displays some of the equipment Joyce Lambert used back in the 1950s.

And under the careful management of the Broads Authority, which was formed in 1989 and promotes people’s understanding of the special qualities of the area in addition to protecting it, this very special part of the world has a very promising future.