Olive Edis and a picture of inspiration

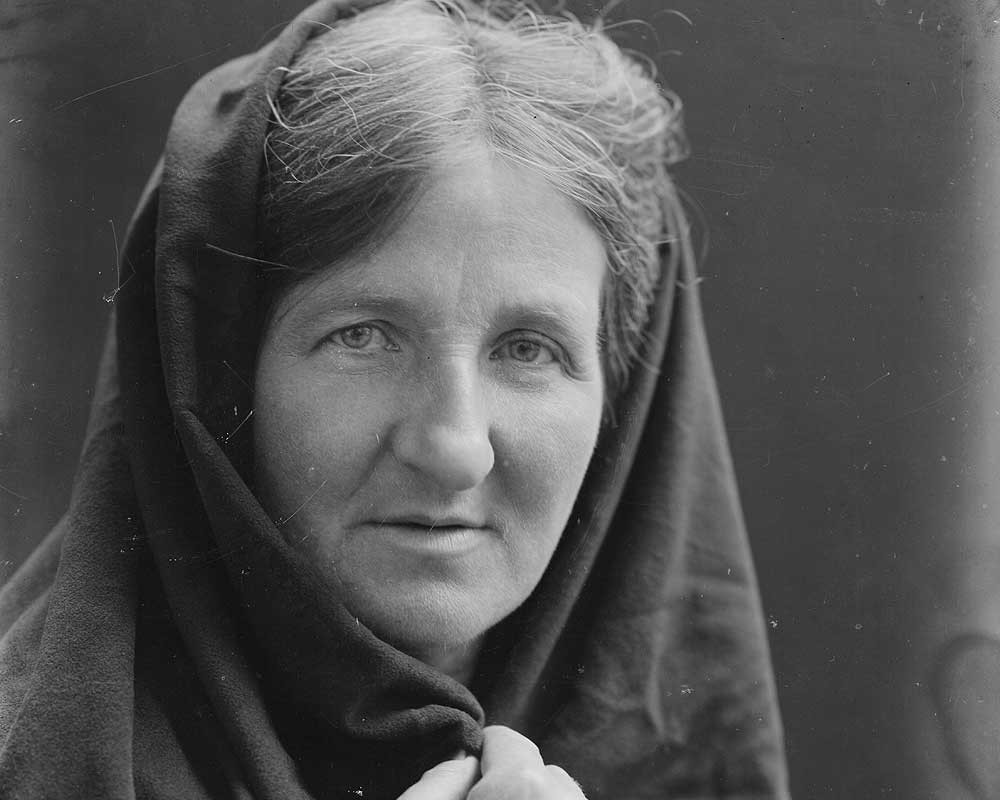

From the fishermen of north Norfolk to the crowned heads of Europe, Olive Edis used photography to document the whole spectrum of life in the early 20th century - and the growing role of women in society

In the collection of the National Portrait Gallery in London is a remarkable photographic portrait of Caroline Murray, daughter of the famous Surgeon General John Murray, who was also a well-known photographer in India. Catalogued as NPGx15507 and measuring only 14cm x 10cm (right), the portrait was taken by Caroline’s 24-year-old cousin Olive Edis - perhaps as a thank you, since the young Olive had been given the camera by her aunt as a present.

At some point over the next few years, Olive herself wrote on the reverse of the photograph:

"My very first attempt at a portrait, which turned my fate in 1900."

The picture isn't just remarkable for the unusually sensitive and natural treatment of its subject - it marks the start of the story of one of the most important photographers of the early 20th century.

Within five years of the portrait of her aunt, Olive had established a successful studio in London and opened a second one in Sheringham, specialising in portraiture - and starting with the Norfolk fishermen and women around her.

She became one of the first women to use the new colour technique of the 'autochrome' - and won a medal from the Royal Photographic Society in 1913 for her image Portrait Study.

In 1918, the Imperial War Museum commissioned Olive to record the vital work being carried out by women in war-torn France and Belgium - a project that would see her taking three cameras on a 2,000 mile journey in March the following year to document the emergence of women into a male-dominated world. She also became the first British woman to be appointed as an official war photographer.

At the height of her career, Olive Edis photographed the full spectrum of British society, from local fishermen and their families to prime ministers (no less than four of them), European royalty, the first woman to take her seat in Parliament (Nancy Astor), and the most notable scientists, artists and writers of her day. She even took some of the earliest colour photographs of Canada.

By the time of her death in 1955, Olive Edis was widely recognised as a quite exceptional portrait artist, a pioneer of new technologies, and a successful business owner.

Alistair Murphy is both curator of Cromer Museum and of the Olive Edis Collection, and having spent the best part of ten years scanning and cataloguing the world's biggest collection of Olive's prints, glass plates and autochromes, he has no doubt of her significance.

"I don't think it's possible to overestimate the importance of Olive Edis," he says. "If you had to make a list of the five most important residents of Norfolk in history you'd have to include people such as Horatio Nelson, Edith Cavell and Elizabeth Fry - but your list wouldn’t be complete without Olive Edis."

She was a woman very much of her time - and ahead of it in many ways.

"The old 'world order' completely changed around the time of the First World War, and it affected every level of society," says Alistair. "Women didn’t just get the vote, but they were coming to the fore in industries and professions that had long been dominated by men. Not only was Olive Edis documenting that change across all social classes through her photography, she was also proving that a woman could use the medium better than most of her male contemporaries. Her work is quite extraordinary."

Just how extraordinary was brought into sharp focus (in a very literal sense) three years ago, when Alistair was involved in a BBC documentary that explored the question of why Olive Edis had (to date) failed to receive the recognition she deserved.

I don't think it's possible to overestimate the importance of Olive Edis. If you had to make a list of the five most important residents of Norfolk in history you'd include people such as Horatio Nelson, Edith Cavell and Elizabeth Fry - but your list wouldn’t be complete without Olive Edis.

World-famous photographer John Waddell (better known globally by his middle name of Rankin) travelled to Cromer and used one of Olive's own cameras in her original studio to take a portrait of the actor Bernard Hill. It was the first time the camera had been used in 50 years.

"You have to remember that Olive's cameras are essentially a box with a hole at one end," says Alistair. "Rankin is one of the most highly-acclaimed photographers in the whole world and it was as much as he could do to get an acceptable image! When you look at the technology she was using and consider the quality of her photographs the achievement of Olive Edis is absolutely incredible."

But it's not all in the technique. Very few people have ever liked having their photograph taken, and although public figures and famous figures may be used to being in the limelight, the same can't be said for local fishermen. All the subjects of Olive Edis' portraits exhibit a genuine intimacy and authentic casualness - an aspect which must have come from her presence behind the camera.

"Since we opened the new displays at Cromer Museum two years ago, the interest in Olive Edis and the appreciation of her work has grown significantly," says Alistair. "She was a unique talent, and we're very privileged to have a unique collection of her images here."

Cromer Museum is adjacent to the church of St Peter and St Paul on the town’s Tucker Street. Visit www.museums.norfolk.gov.uk/cromer-museum for the latest information on opening times.