The less-than-heroic life of the ‘other’ Lord Nelson

The death of Horatio Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar was seen as a national tragedy, but in Norfolk his older brother realised he’d soon be receiving the prestige, power and wealth he had wanted for so long

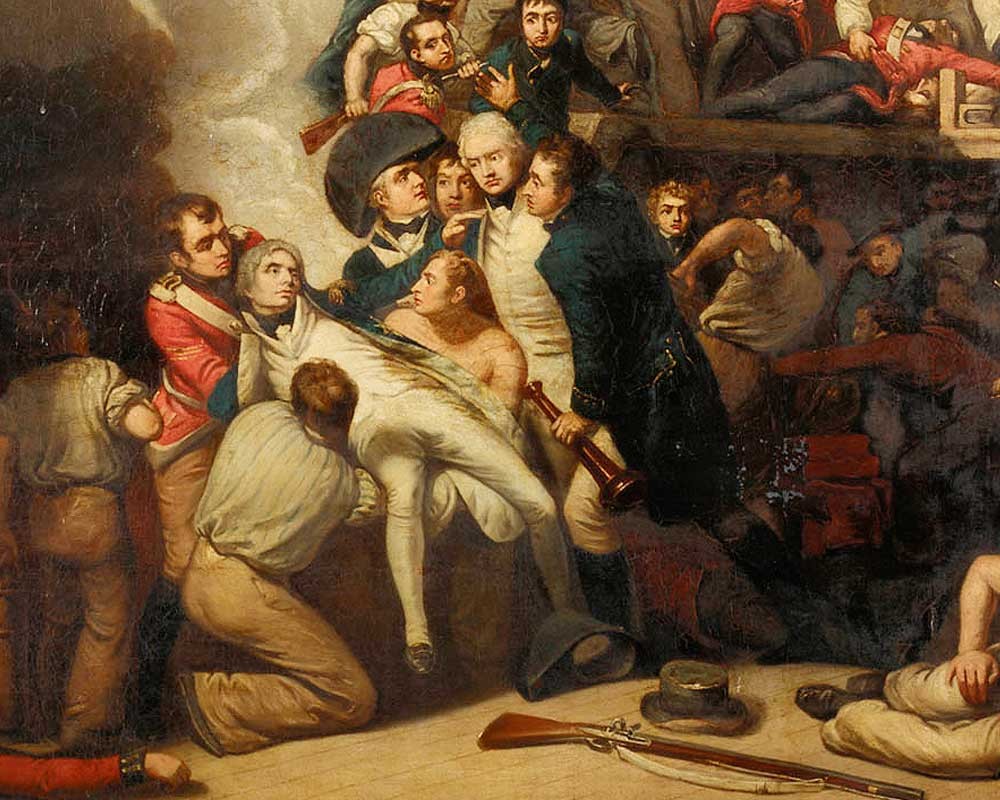

At 4pm on Monday 21st October 1805, Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson, Viscount and Baron Nelson of the Nile and of Burnham Thorpe and of Hilborough in the County of Norfolk, Duke of Bronte in Sicily, to name but two of his titles, died at the Battle of Trafalgar.

At that exact moment, a chubby 48-year-old rector in the tiny village of Hilborough who’d never fired a shot in defence of his country (or told an entire fleet that “England expects that every man will do his duty”) became the new Lord Nelson. At long last, the ambition of William Nelson was fulfilled. Years of nagging his illustrious younger brother for preferment to a bishop’s palace (at least) had failed, but with the death of England’s hero, William Nelson was literally “made up”. After all, inherited titles need someone to inherit them – and in the absence of a son the nearest male relative will serve, no matter how undeserving they may be.

William was never popular with the rest of the large Nelson family, and was despised at best by Fanny Nelson, Horatio’s refined wife, who was the daughter of a well-to-do planter in the Caribbean. In fact, she thought him the “roughest mortal surely who ever lived.”

Hilborough was the home parish of generations of Nelson clergymen, so William naturally ended up there. No merit was needed, after all. Indeed, William Nelson was always called

“The Rector” as if he was too odd a creature to actually have a name.

After his brother’s famous victory at the Battle of the Nile in 1798, he expected (on a daily basis) to be made a bishop, eventually writing to Horatio ”What must we think of the gratitude of ministers who pass over your Brother almost every day? No longer ago than last week, Two deaneries and Two Prebendal Stalls were disposed of – but the name of Nelson is not even thought of by [Prime Minister] Mr Pitt.“

He knew it was onIy through his family connection to the great admiral that any chance of a better position would come.

In October 1800, when Horatio Nelson returned from Naples with Sir William and Lady Emma Hamilton (therein lies a tale), ‘the Rector’ and his wife, well-briefed by the gossip columns in the newspapers and realising which way the wind was blowing, abandoned Fanny and toadied up to Emma – with whom Nelson had by then become completely besotted.

Not only did they attach themselves to Nelson and the Hamiltons (which bored Sir William immensely) but they were now resolute in their attack of Fanny. They were frequent guests at 23 Piccadilly, the house Lord Nelson shared with Sir William and Emma in a very public tria juncta in uno (‘three joined in one’) – the Latin phrase being chosen by themselves.

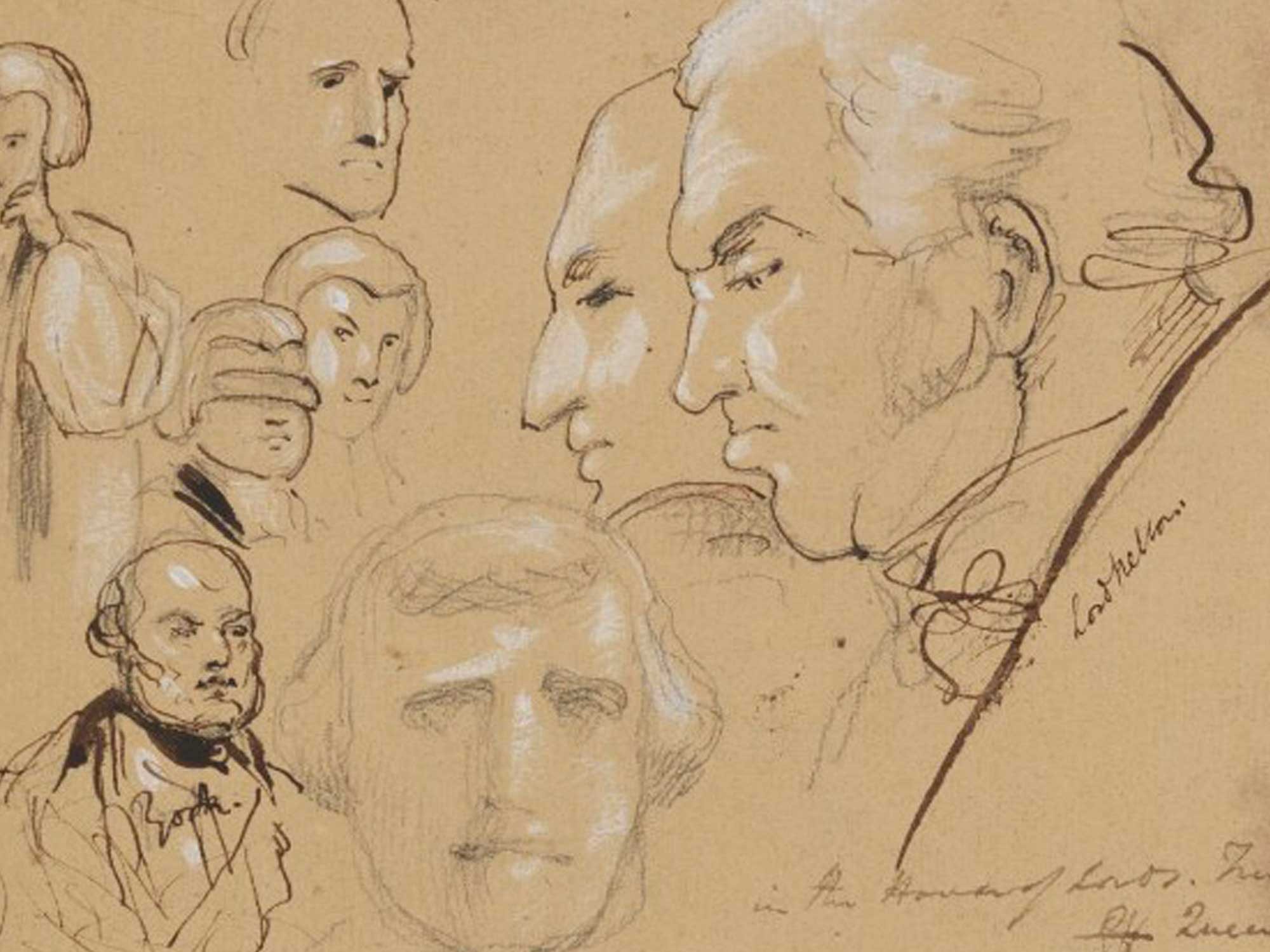

Sir William himself put pen to paper to congratulate Nelson on his victory at Copenhagen, but couldn’t help mentioning his annoying sibling, commenting that “your Brother was more extraordinary than ever. He would get up suddenly and cut a caper – rubbing his hands every time the thought of your fresh laurels came into his head.”

After Nelson’s death at Trafalgar, Parliament had no living hero to elevate to high office in grateful thanks for vanquishing the French and Spanish fleets. So, on 9th November 1805, William finally got the attention he felt he deserved, being named ‘Earl Nelson of Trafalgar’ in honour of his late brother’s achievements.

He had already inherited Nelson’s Sicilian title of Duke of Bronté given by King Ferdinand of Sicily and, as if this wasn’t enough, Parliament granted the former rector a lump sum of £99,000 (£100 million at today’s values) to purchase a suitably stately home – meaning the imposing property at Standlynch Park in Salisbury would soon be re-named as Trafalgar House.

William’s change in fortune didn’t end there. He also received a rather useful pension of £5,000 a year – some £3.7 million at 2019 values!

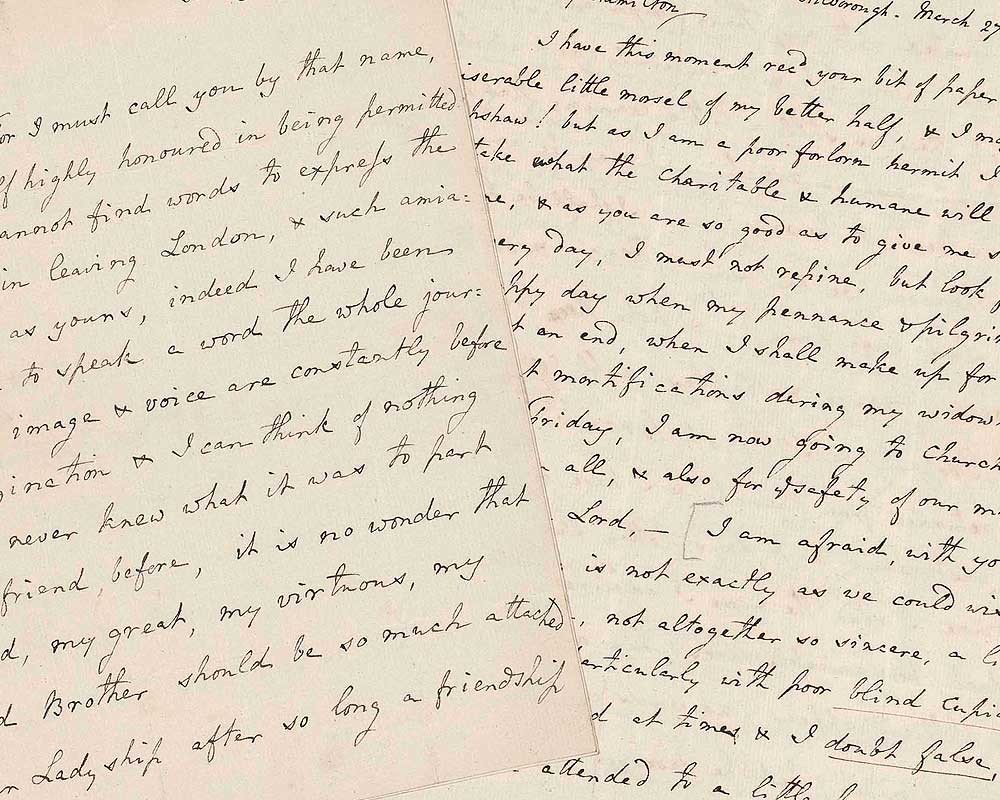

Parliament also voted grants of money to Nelson’s immediate family (his two sisters received £15,000 each) and his ever-loyal wife Fanny received £2,000 – which the widow was going to need as she planned to sue her recently-elevated brother-in-law for the annuity willingly given to her by Nelson.

One of the law officers involved in the dispute wrote:

“I love Lady Nelson dearly and admire her dignified pride and spirit, which, I trust, will not be subdued by the infamous conduct of her late husband’s brother, sisters and their husbands – all of them vile reptiles.”

The rector-made-earl then showed his true colours, abandoning Lady Hamilton as easily as he’d originally supported her – ignoring her descent into alcoholism, poverty and a lonely death in Calais. After all, he’d finally received what he felt he’d been entitled to for so long.

He also seemingly (but perhaps not surprisingly) forgot his promise to look after Horatia Nelson – the daughter his brother had fathered with Emma Hamilton.

Horatio Nelson’s friend Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood (who’d commanded the first ship to engage the enemy at the Battle of Trafalgar) had no doubts about William Nelson.

“Nothing in him like a Gentleman,” he wrote. “Here has Fortune, in one of her frisks, raised him, without his mind or body having anything to do with it, to the highest dignity.”

Within a year of his wife Sarah’s death in 1828, William Nelson married a young woman Hilare Barlow – young being the operative word, as she was 46 years younger than her new husband. If it was an attempt to establish a new Nelson dynasty, it failed. William died in February 1835 without a male heir, and all his British titles passed to Thomas Bolton, the son of his sister Susannah. The Sicilian dukedom of Bronté passed to his daughter Charlotte.

A member of the family remained at Trafalgar House for over a century, before the 5th Earl Edward Nelson sold the estate to the 11th Duke of Leeds in 1948.

Actions speak louder than words, but in this case they all say the same thing. By all accounts, William Nelson was a particularly unremarkable man – whose relationship to a national hero ensured he had a quite remarkable story nevertheless.