A look at King’s Lynn during the plague years

In less than 10 years the Black Death killed up to 65% of Europe’s entire population, and it continued to be a threat for the following 300 years. Dr Paul Richards examines how the deadly disease affected King’s Lynn

In October 1347 a dozen trading ships from Genoa docked at the Sicilian port of Messina after a long journey through the Black Sea. Most of the sailors were dead and the remainder were seriously ill, and although the locals did what they could to help, the town soon learned at first hand what the ships had brought with them. Within weeks the Black Death had spread across Italy and raced through Europe, arriving in England a few months later.

Within four years, almost 50% of Europe’s entire population had been lost to the plague and its variants, and the disease would continue to strike terror around the world for centuries to come.

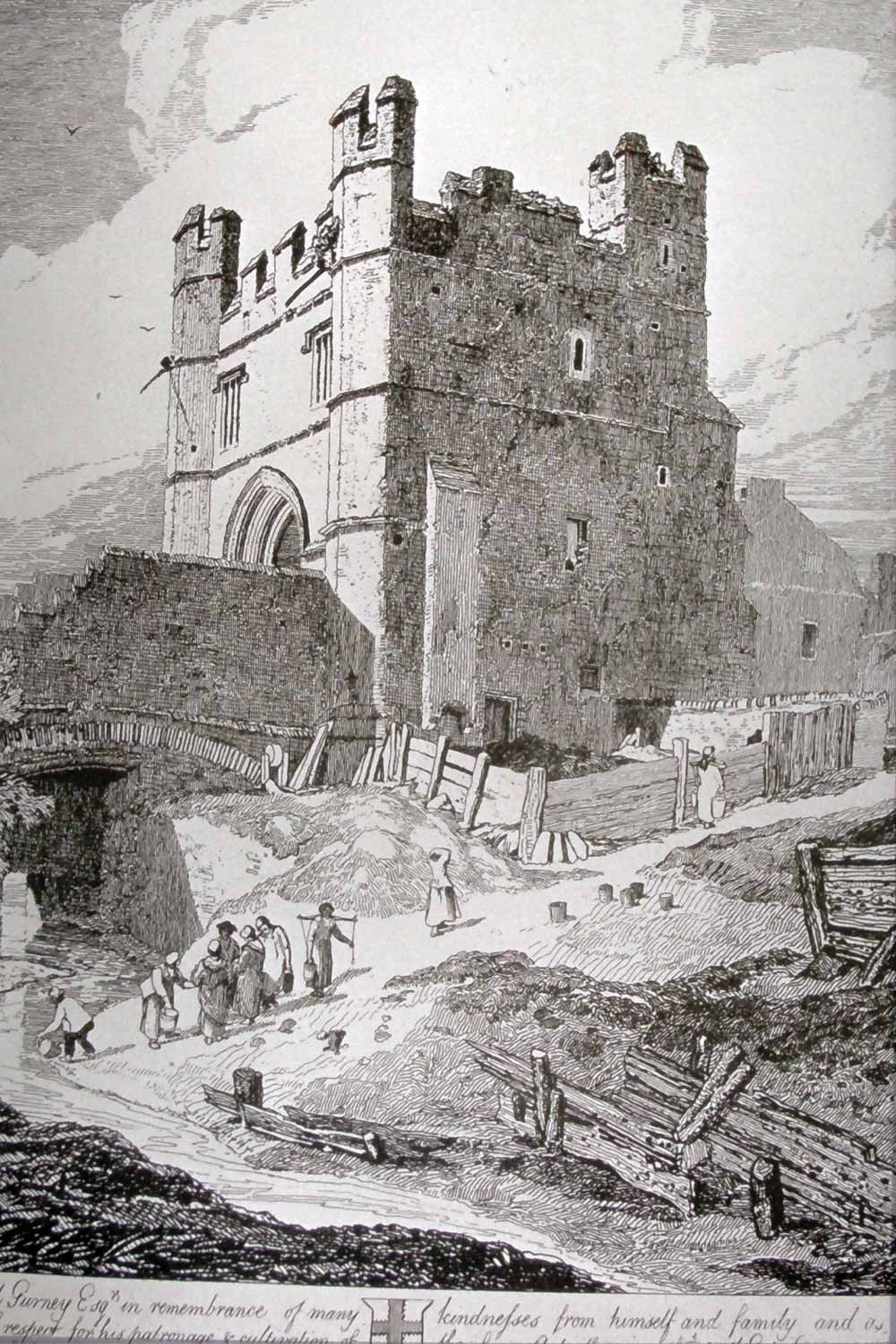

By the time Bishop’s Lynn became King’s Lynn by an Act of Parliament in 1537 its population of about 5,000 probably thought the worst was behind them, but as an important port with many international connections the town frequently suffered from outbreaks of the plague which often lasted several months.

The onset of the plague was a disaster for the town’s economy as death rates and sickness increased. Unemployment rose as workplaces and taverns closed, although the weekly markets continued for healthy citizens who had no other access to food - and the daily catches of fish by the Northenders became vital.

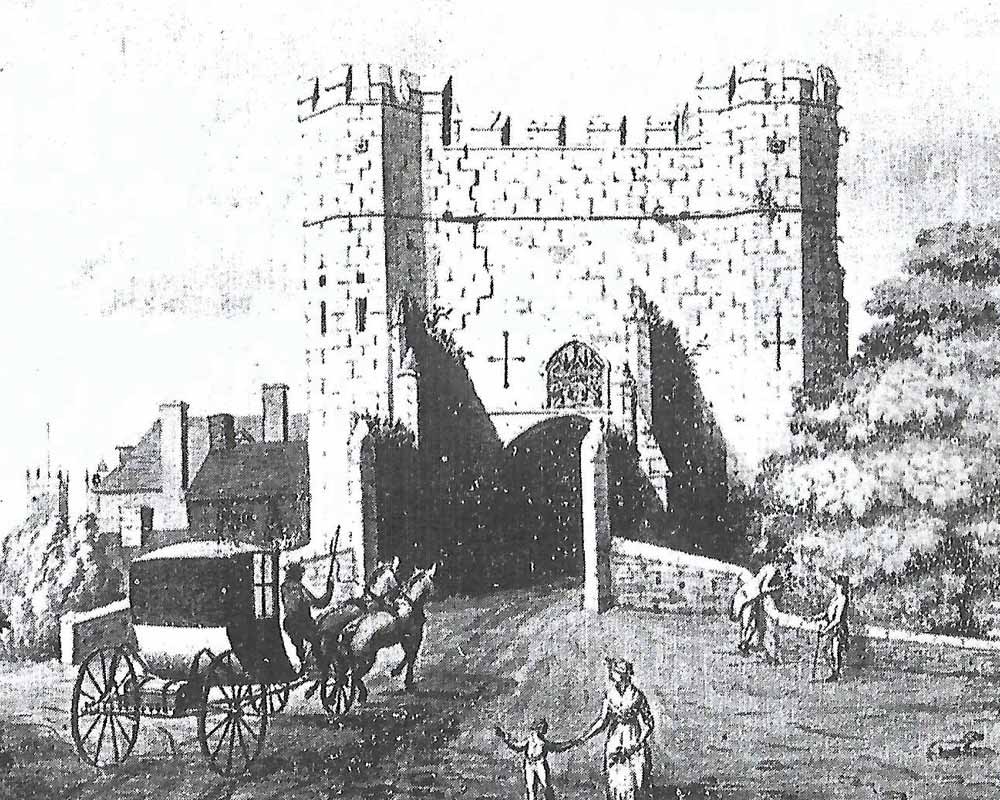

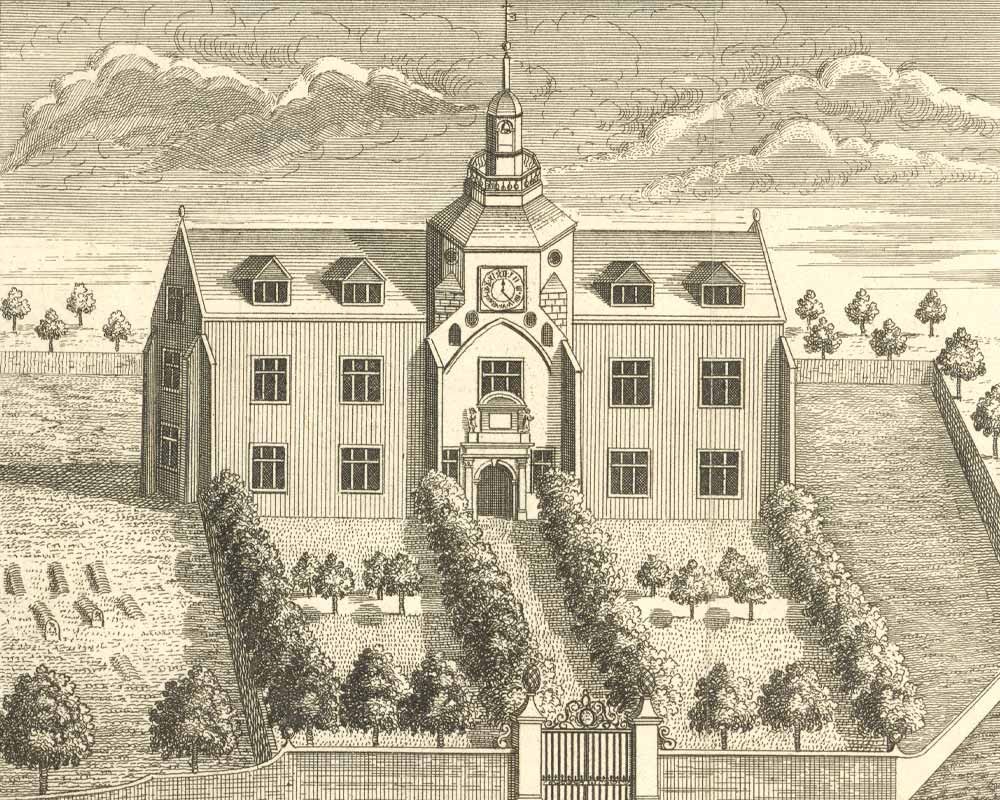

From the Town Hall the mayor and aldermen ordered people to stay at home and issued “stay at home” directives. Quarantines were put in place to stop the spread of the disease, the authorities appointed wardens to enforce the regulations, and neither of Lynn’s annual fairs were held in 1540 because such events could double the town’s population, increasing the opportunities for the disease to spread.

The next major outbreak of plague occurred in 1584, when a special tax was levied for the relief of victims and their families and the town’s February Mart was permanently moved to the town’s Tuesday Market Place because of overcrowding in Norfolk Street.

Another outbreak 13 years later saw the deaths of some 6,000 Lynn residents (around 10% of its entire population) and over 200 were interred in St James burial ground adjacent to the town’s workhouse where the sick were hospitalised - a single window and section of wall still exists in the nursery school playground in St James Park.

Little more than four years later, the plague paid another visit to Lynn in 1602, although it was concentrated in the North End. In October of that year the council ordered that residents of the area should be isolated and their food conveyed to them. Shortly after that another outbreak saw the town’s grammar school “broken up” to stop the spread of infections.

It wasn’t just the threat from within that was of concern.

Council minutes from July 1625 report an outbreak of plague in Cambridge, and the mayor ordered the gates of King’s Lynn to be shut and a watch kept along the river to prevent sailors disembarking. Innkeepers were told not to accommodate people from other towns on penalty of having their premises closed.

A similar outbreak in Cambridge in April 1630 saw the town’s gates closed to all incoming traffic again, but when the disease was found in the town two months later Lynn’s cats and dogs were shot as likely carriers.

Six years later the threat was coming from the north, as “the pestilent sickness” raged in Newcastle during the spring of May 1636. Colliers frequently sailed to Lynn in convoy delivering coal for its distribution to eight English counties, which was an obvious cause for concern.

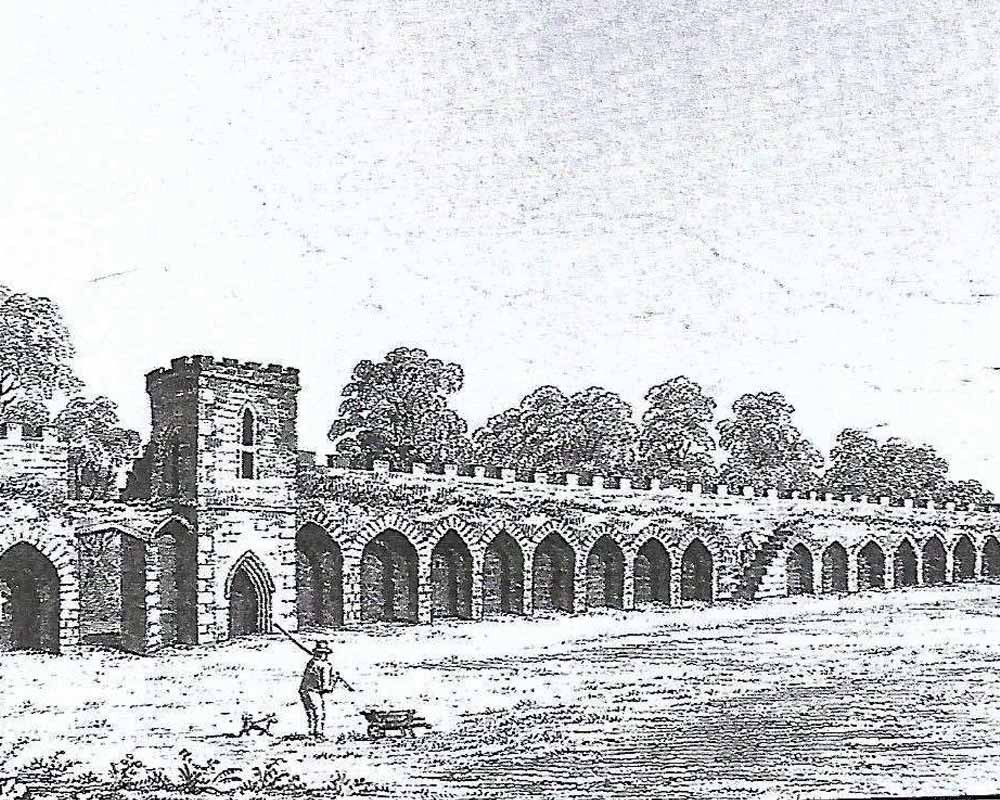

No one from Newcastle or any other “infected place” was allowed to come ashore for 14 days, a regulation enforced by the council’s porters. Wooden booths (“pesthouses”) were erected outside the town walls for plague victims, and a special doctor was paid by the Town Hall to treat the sick until it “pleased God” to end the epidemic - the containment orders were only cancelled the following year

Less than a decade later, armed guards were being posted at the gates of King’s Lynn to keep out “rogues and vagabonds” as well as sick people during the Mart, and a few weeks later came news of a new outbreak of plague in Sunderland. Ships arriving in Lynn were quarantined and sheds to house the sick were built against the town walls. It was reported that traders were “forsaking” the town.

The national ringing of church bells on the “thanksgiving day” of 14th October 1646 was only a short-lived celebration. The Lynn Mart was held successfully in February 1665, but by June the plague had devastated London (10,000 people would eventually die) and it returned to King’s Lynn over the summer.

Once again the town’s gates were shut to incoming traffic. Boats from Cambridge and Peterborough were prevented from landing goods on Lynn’s quaysides. Booths were once again erected against the town walls “to entertayne” infected people - and visiting relatives were deterred by armed guards.

It was the last major outbreak of plague (although ships were still being quarantined in King’s Lynn as late as September 1743) and the town wouldn’t experience anything like it for over 350 years - until the World Health Organisation named the disease caused by the virus SARS-CoV-2 as Covid-19 in February 2020.

The plague had a huge impact on social structures, working practices, economics, architecture and literature - and only time will tell if we’re currently undergoing a similarly widespread and long-lasting upheaval.