The local man who helped end slavery

Thomas Clarkson was born in Wisbech and a winning entry to an essay-writing competition propelled him on a path that would consume the rest of his life and eventually result in the abolition of slavery

We’ve heard and read a lot over the last year about our 19th century public sculptures of the great and the good - especially as we re-evaluate our judgements of what constitutes ‘great’ and what counts as ‘good’.

Standing in the centre of Wisbech and bearing a natural resemblance to the Albert Memorial in Hyde Park (it was designed by the same architect) is a monument featuring a statue of a local man called Thomas Clarkson.

This year marks the 174th anniversary of the death of this “moral steam engine” (as he was once described) and in the fight to abolish slavery it’s unlikely anyone worked harder or took more personal risks.

Born in 1760, Thomas Clarkson’s father was a priest and master of Wisbech Grammar School, who gave both his sons a particularly good education.

While his brother John would become a famous naval officer, Thomas was all due to follow in his father’s religious footsteps when he decided to enter a Latin essay-writing competition while at Cambridge University.

The subject was anne liceat invitos in servitutem dare - which translates as “is it lawful to make slaves of others against their will?”

The young Clarkson read and researched everything he could lay his hands on about slavery, and even met and interviewed people with personal experience of the global trade. His essay won first prize and it changed his life.

On his way home from London after having read his prize-winning essay in public, Clarkson had a revelation. The more he thought about it, the more he became convinced that he was dealing with far more than an academic exercise.

“A thought came into my mind that if the contents of the essay were true,” he later wrote, “it was time some person should see these calamities to their end.”

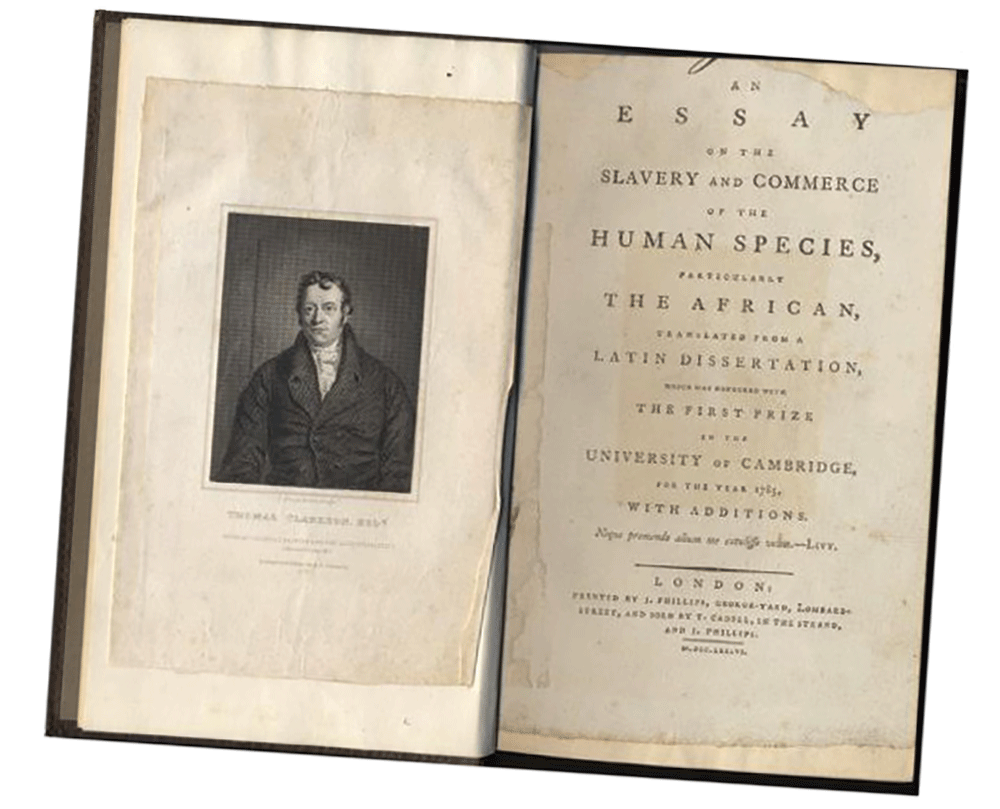

Translating his work into English, Clarkson published it as a pamphlet in 1786 with the rather unwieldy title of An Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, particularly the African, translated from a Latin Dissertation.

He had a natural gift for writing, encouraging Jane Austen to claim to be “in love with the author” despite the fact her family was friends with several prominent slave owners.

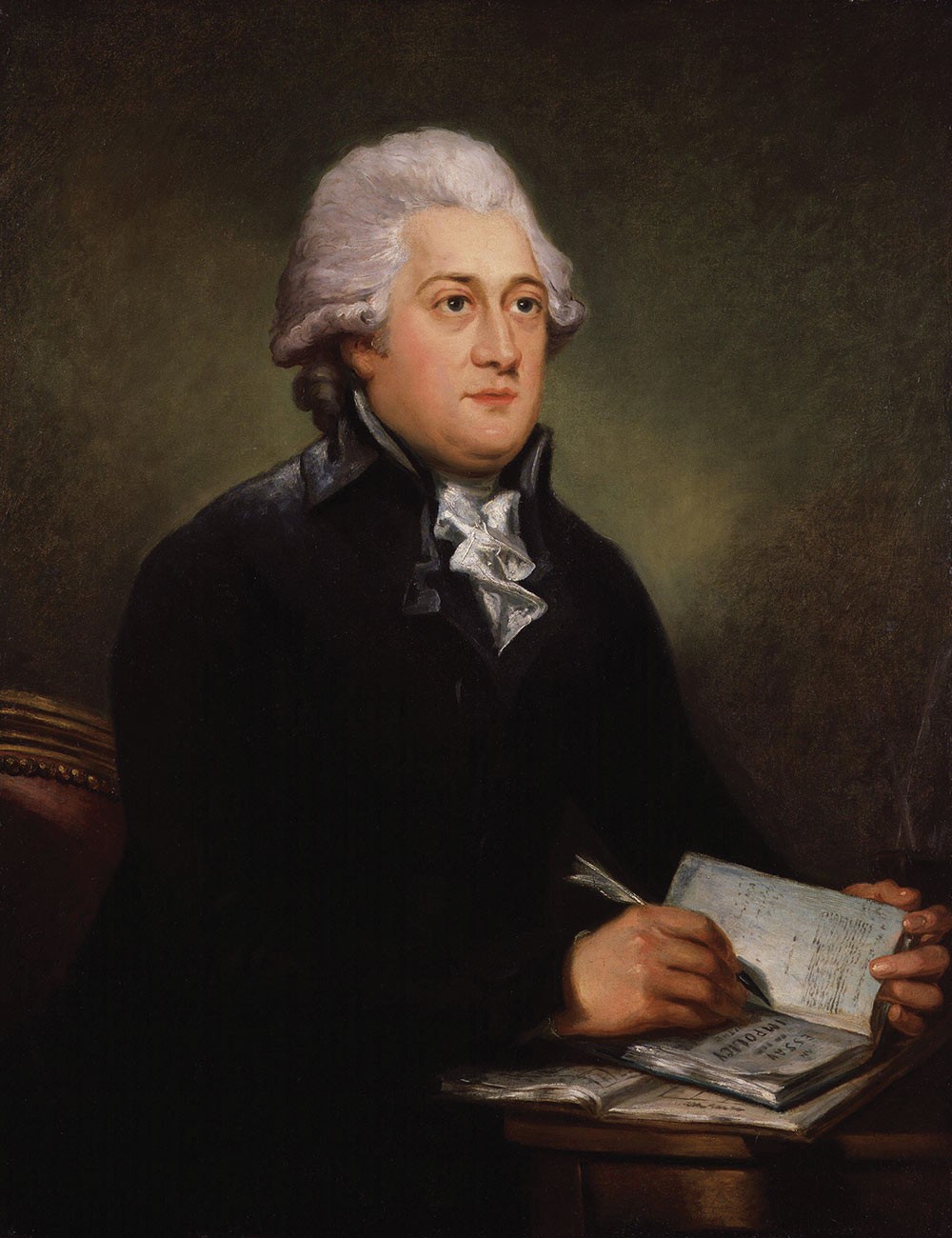

In May 1787, together with 11 other men Thomas Clarkson founded the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, persuading the MP for Hull – a certain William Wilberforce – to speak for them in Parliament.

Where Clarkson was a genius with a pen, Wilberforce was a brilliant orator, and his performances would establish him as the public face of Britain’s abolition movement - even though his remarkable speeches were based on evidence gathered and supplied by Clarkson.

Not that Clarkson sat in his study consulting dusty volumes and archives. He travelled almost 40,000 miles around Britain, finding witnesses, obtaining first-hand accounts, recording facts and figures, and putting his life in danger. When he arrived in Liverpool (one of the country’s major ports for the slave trade) he narrowly escaped being murdered by sailors who’d been paid to kill him - before receiving more abuse and threats of violence and when he took his campaign to France in 1789 on the eve of the French Revolution.

When the first abolitionist bill reached Parliament in 1791 it was defeated 163-88 - a crushing blow for the anti-slavery activists, but something of an incentive for Thomas Clarkson. He continued travelling all over the place, giving speeches wherever he could, and helping form local abolition groups.

But the effort took its toll on his health, and after another Parliamentary bill was defeated in 1792 he took a well-earned break, marrying a woman from Bury St Edmunds and moving to the Lake District with a view to becoming a farmer.

He missed his true calling however, and returned south in 1803 to renew his campaigning efforts - which were rewarded with the passing of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act in March 1807. However, the law only applied to the commercial trade itself. Slavery was still legal and for the rest of his life Clarkson continued to promote the anti-slavery message. Even at the age of 67 he covered some 10,000 miles and tried to encourage Parliament to bow to changing public opinion.

By 1833 it had been almost 50 years since Clarkson had written his prize-winning essay, and following a three-month debate in the House of Commons the Slavery Abolition Act was finally passed, giving all slaves in the British Empire their freedom.

At least in theory. Only children under six were truly given their freedom and all other slaves were required to work for their owners for a further six (unpaid) years - a situation Clarkson and his wife campaigned against until its end in 1838.

Thomas Clarkson finally died aged 86 in September 1846 at his home in Playford. He’d spent virtually his entire life turning the abolition of slavery into one of the main political issues of the day, and combined engaging writing with brilliant speeches and an innovative approach to publicity to change people’s attitudes.

And to a certain extent, this man from Wisbech helped change the world.