When local nature paints its own landscapes

The north Norfolk coast contains a breathtaking range of inter-tidal sand and mudflats, salt marshes, shingle banks, sand dunes, brackish lagoons and reed beds - and they’re even more impressive from the air

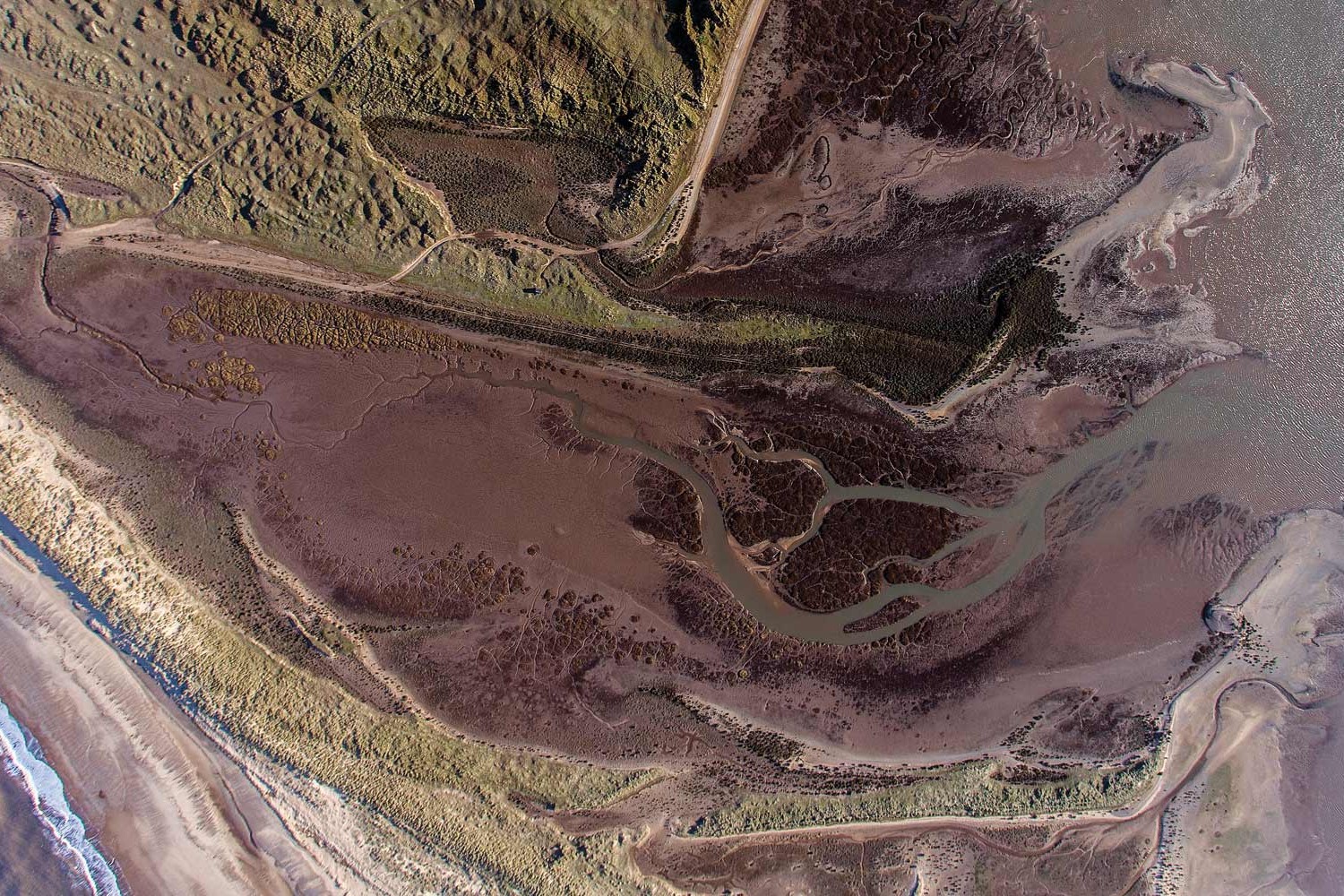

Seen from above as in the photographs here, the salt marshes along the north Norfolk coast are an amazing, other-worldly landscape. The ceaseless tides of the North Sea have carved paths through the marshes creating patterns of tributaries which echo other natural forms like heavily-branched trees, or blood vessels under a microscope.

Although they may look like a deserted and somewhat desolate landscape from this distance, viewed up close they’re packed with plant life, and are a haven for a wide range of bird life.

Salt marshes are coastal wetlands flooded and drained by salt water brought in by the tides. They’re marshy because the soil may be composed of deep mud and peat. Salt marshes are formed by a combination of high tides and sheltered areas like bays or the top of long, flat beaches, or behind spits of land. These sheltered areas minimise wave action and allow seawater to deposit the tiniest, lightest, clay particles. These particles cling to one another in a process known as flocculation and settle to form a mud. The mud is stabilised and then colonised first by algae, and then by samphires (glassworts) and sea aster. The flow of water is interrupted, making further deposition of mud more likely, and a marsh forms and develops.

Once the marsh is well established numerous other species of plants move in and form the area known as the middle marsh. You might find marsh mallow, shrubby sea-blite, salt meadow sedge, or sharp sea rush as well as four species of sea-lavender - including matted sea-lavender, a species now confined to Norfolk within the British Isles.

On areas of raised ground, where inundation by tides is less frequent, sea beet, pungent sea wormwood and the nationally-scarce shrubby seablite grow. And along the edges of creeks where more sediment is deposited by each tide and the ground is slightly higher, characteristic strips of silver-leaved sea purslane can be seen.

Salt marshes aren’t just home to plant life either: they’re also thronged with fish and fowl. They’re rich in mud-dwelling invertebrates, and many marine fish use salt marshes as nursery grounds for their young before they move to open waters. These in turn are eaten by huge numbers of migrant wading birds, some of which raise their young among the high grasses, taking advantage of the sanctuary from predators and plentiful food.

Our coastline is of global importance as a migratory staging ground and wintering ground for northern breeding species such as knot, dunlin, bar-tailed godwit, oystercatcher, grey plover and shelduck. Our salt marshes are visited in winter by brent geese and curlew, and in summer by redshank and skylarks.

Once perceived as coastal ‘wastelands’, our appreciation of salt marshes has changed, and they are now nationally and globally acknowledged as one of the most biologically productive habitats on earth, rivalling tropical rainforests. In fact, salt marshes are now legally protected in many countries.

The salt marshes along the North Norfolk coast are under a number of legal protections, to maintain them as such a special habitat, and to keep them as such a beautiful, peaceful place to visit. 7,700 hectares (19,027 acres) of the coast from just west of Holme-next-the-Sea to Kelling has been designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). SSSI status means that Natural England support landowners to manage these sites in a way that conserves their special features. The marshes are additionally protected through Natura 2000, Special Protection Area (SPA) listings, and part of the Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). The North Norfolk Coast is also designated as a wetland of international importance on the Ramsar list and most of it is a Biosphere Reserve.

The preservation of the salt marshes has been largely thanks to the organisations that have bought and cared for different parts of them over the past 90 years: the Norfolk Ornithologists’ Association (Redwell Marsh), Norfolk Wildlife Trust (Cley Marshes and Holme) and RSPB (Titchwell Marsh), but especially the National Trust. It holds the lion’s share including the more famous portions – Scolt Head and Blakeney Point – but also the Brancaster, Stiffkey and Morston salt marshes.

So take in these beautiful photographs, and reflect that behind their peaceful, even desolate appearance, there’s a whole world of wildlife bustling behind it, and an even busier world of human endeavour preserving and protecting it.